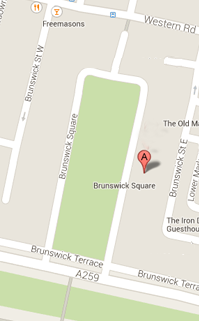

19 Brunswick Terrace

19 Brunswick Terrace on the corner

On 20 July 1825 the local master builder George Cheesman Senior leased the plot of 19 Brunswick Terrace at the junction with the projected Brunswick Square and started erecting a grand house on it. He no doubt had his eye on the rents the higher aristocracy and gentry would pay him to sojourn there through the fashionable parts of the year.

He almost certainly wouldn’t have imagined that it would also house for various periods a hair-oil business dynasty; a Government mover and shaper of Victorian Britain’s booming railways system; a serially adulterous and wife-beating Yorkshire moneylender; a hugely successful pioneer of the Australian gold mining industry; and a former child refugee from the Polish pogroms done good. All in their own way representing the flow of economic and social change surging through Brighton and Hove as much as anywhere else in Britain over the following 100 years and on.

It’s unlikely Cheesman himself ever lived at Number 19. He is recorded as “owner and occupier” in the Poor Rate Books from 1841-1850. But even during a long lull through 1841 when unusually No.19 isn’t mentioned in the local newspapers’ long lists of fashionable arrivals and departures, the census that year shows only two people present - Mary Jarratt, 25, of Sussex, and Caleb Marshall, 30, born in Ireland. These were most probably caretakers.

Cheesman appears to have been very much capo di capo of a large and long-established Brighton family with their hands in various businesses from dairies to fisheries. According to its biographer, John Hoare, they all tended to live and operate in and around Kensington Street in the North Laine even through the area’s own clearance and development. And there Cheesman remained – for a long period at No.34 - running his own significant interests, sometimes with his sons, not only in building and property investment but also cement-making, coal merchanting and a fishing fleet, until his death in 1866.

Besides, 19 Brunswick Terrace was clearly meeting his expectations for top-end, short-term renters coming for their fashionable stays in Brighton. One particular reason, which surely wouldn’t have escaped his builder’s eye, was that in construction as well as visual terms it is the substantial cornerstone joining and supporting the east side row of Brunswick Square houses running downhill to the shore toll road and the terrace stretching eastwards along the seafront. This meant that it would be bigger not only on the outside than others on the terrace and indeed many in the square, emphasised by its more prominent columns and plinths, but also inside, including 11 bedrooms plus dressing rooms above the ground and first floor. So, it would particularly appeal to the wealthier sort who along with family and friends preferred to bring most if not all their own household of servants to attend them.

An additional attraction over virtually all the other houses in Brunswick Town was that it gave them inspiring sea views both to the South and West (also ensuring none of the principal rooms needed windows at the back and so avoided awfully unpleasant views onto the kitchen yard and servants’ quarters).

Richard Colley Wellesley, Marquess Wellesley (1760-1842) - Royal Collection by Sir Thomas Lawrence

One of the first occupiers, according to Judy Middleton’s Hove in the Past website, was Richard Colley Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, arriving in September 1828. He had only recently resigned from the high and politically sensitive post of Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, trying to reconcile the country’s Catholics and Protestants unsuccessfully although - or because? – he was of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy himself. He had also been British Foreign Secretary.

But his political and historical importance stems much more from his time between 1797 and 1805, when as Governor of Madras and Governor-General of Bengal he greatly expanded Britain’s rule across India. He had been increasingly aided by his brother Arthur who, in crucial battles there against local princes and the French, started building a military career that culminated in victory over Napoleon at Waterloo and the title of Duke of Wellington.

Sadly, well before he came to Brighton, the Marquess had grown increasingly bitter that his contributions to the nation had not been recognised enough, and particularly because they had been overshadowed by his brother’s.

Marianne Wellesley (née Caton), Marchioness Wellesley

Creative commons licence

His one solace seemed to have been the Marchioness, Marianne. A wealthy widow from Baltimore who had come to Europe for her health, she had married him in 1825 despite her family’s concerns about his previously scandalous life (among other things the several children he’d had with a French actress before marrying her). “Much of the calm and sunshine of his old age can be attributed to Marianne," says his biographer, Iris Butler.

The Wellesleys stayed only until February 1829 – he going to have a second brief stint in Ireland before giving up political life, she to become a Lady of the Bedchamber to William IV’s Queen Adelaide. But their place was almost immediately filled by what over the following 60 years would be a steady stream of other mostly high aristocracy and gentry taking residence for various periods through the year. The second half of winter seems to have been particularly popular, probably reflecting the need to escape the increasingly noxious smoke of London and avoid the enmired roads to their country estates, when both would be at their worst. And those who could do arranged to take up residence for the same time each year.

Lady Trollope was a case in point. Her husband Sir John Trollope, sixth Baronet of Casewick in Lincolnshire, had died in 1828 in a riding accident. From 1833 she features regularly in the local social news as another late winter visitor to Brighton, usually until May, between living at the country estate at Uffington in Lincolnshire and in Great Cumberland Place in Westminster. She seems to have favoured different houses along Brunswick Terrace but settled on No.19 the year before the 1851 census listed her there as head of household and, under the heading “Rank, Profession or Occupation”, “Baronet’s Widow”. With her were her two daughters – one married - and nine servants of which only one, the house maid Harriet Williams, might have been local.

The only suspicion that might be laid against Lady Trollope is that she seems to have misstated her date of birth in the census as 1801. She wouldn’t have been the only lady of society, then and now, to want to conceal her true age. But cutting 21 years was pushing it. And subsequent censuses and other records show her daughters Matilda and Laura were born in 1805 and 1807 respectively, which would have made her Ladyship an unfeasibly young mother. Their birth years are therefore also flatteringly put back 19 years in the 1851 census. However, anyone seeing that and remembering Matilda’s much reported-on marriage in 1838 to the owner of Leeds Castle in Kent, Charles Wickham Martin, might have wondered that in in modern Regency times there were still 14-year-old brides.

Leeds Castle. Source Wikimedia, Creative commons licence

Matilda lived at Leeds Castle until her death in 1876, six years after her husband, and was even portrayed by a society photographer very much in the role of its chatelaine. Her sister Laura would remain single just a year after the 1851 census, marrying Joseph Sidney Tharp of Chippenham Park in Cambridgeshire. His father had claimed over £53,000 – worth almost £6 million today - in government compensation for his plantations in Jamaica after the abolition of slavery in 1835. They were wed in the same fashionable church in Marylebone, London, as her sister and Charles had been. Laura died in 1877, a year after Matilda. She was buried in Chippenham “with a large crowd attending”, next to Joseph and their eldest son, who had died two years earlier within six weeks of each other.

Lady Trollope had returned to 19 Brunswick Terrace in January 1852 and in the next three winters. She might well have been coming back as usual in January 1856, but she died the previous 23 December at her London residence, aged 75. She was buried back at Uffington.

For all the winter visitors such as this, the other seasons also saw a regular flow of rich, top-class comers and goers at No.19, as announced in the local social columns. Henry FitzGerald-de-Ros, holder of the oldest baronetcy in the English peerage, occupied it for a whole nine months until May 1833 before returning to London, as many did following the Royal Court. Unfortunately, three years later this master whist-player was caught cheating at cards at a gentleman’s club in London, from which his health as well as reputation never recovered and he died unmarried and without children in 1839. It has been suggested Charles Dickens used him partly as the model for that arch-swindler, fleecer of gullible young men and seducer of vulnerable young women Sir Mulberry Hawk in Nicholas Nickleby, which was first published as a serial in 1838-9.

Anther summer sojourner was the first Earl of Munster, eldest of the 10 children the future William IV had had with his mistress Dorothea Jordan - another actress. In 1836 he and his family took both 19 and 18 Brunswick Terrace from March to October (see also 26 Brunswick Terrace on this site).

It's unclear when the Rev. Thomas Scutt, owner of the land on which Brunswick Town was built and from whom Cheesman bought the original lease, handed over the freehold for No.19 as well. But a petition in the Court of Chancery in 1872 shows it was held by a Henry Harrap in 1861 when he passed it in a codicil made to a trust for City watchmaker Robert McCabe and Emily Bennett for their marriage that year. There is no sign of the lucky couple ever staying at the house. Instead, it seems that at the time of their nuptials the property was already leased long-term as a holiday home by the Rowland family from the affluent Lewisham-Sydenham area of South London.

Certainly, on 7 April 1861 the census that year found 72-year-old Alexander Rowland – listed as Head of the Household - and much of two further generations all gathered at No.19. His father, also Alexander, had become a celebrated barber in Jermyn Street at the centre of late 18th-century London’s gentlemen’s clubland. And he had founded the family’s fortune on his revolutionary concoction he promised “preserves, strengthens and beautifies the hair”, macassar oil – that bane of every Regency and Victorian housekeeper’s life, until someone invented the piece of linen to protect the padded backs of armchairs from resting oily heads, the anti-macassar.

Rowlands Macassar oil

Creative commons licence © The Trustees of the British Museum.

According to the family’s modern-day biographer Richard Rowland, Alexander I was an early master of marketing promotion: he was one of the first two manufacturers to advertise nationally in the press. But Alexander II was even more so, creating a whole mythology around its origin, proclaiming its use by crowned heads across Europe and declaring the patronage of Queen Victoria herself over the front of his warehouse in London’s Hatton Garden.

However, by 1861, after running the business a good 30 years and retiring from it 10 years earlier, he was ailing. A genial old man, he would die in the summer back in his extensive Sydenham home surrounded by his beloved rose gardens and family. The census shows his nurse, 50-year-old Elizabeth Mitchelson, was attending him at No.19. He would leave her a small bequest. This may have been particularly useful as she appears to be a patient at the Bristol Eye Hospital in the 1871 census. In the next one she is recorded blind and living with her sister in Clifton and she died two years later.

Alexander II’s son Alexander William had taken over running the business in 1851, aged 40. That same year his wife died giving birth to the last of their eight children. Alexander William had first met Henriette von Ditges in Germany when, despite his “trade” origins, he was furthering his education on a Grand Tour and other excursions across Europe like any young gentleman. He would follow his father’s custom in fostering a lively atmosphere at home, including gatherings of art-loving friends and encouraging his children to study and enjoy paintings.

A glance at the 1861 census entry conveys how lively it might have been, even without the holiday spirit. Alexander William is there, along with his younger unmarried sister Sophia whom he recruited to help care for the children after their mother’s death; his four daughters, ranging from 11 to 15 years of age (his three sons were perhaps still away at school); two female friends from London, one of which at 13 is accompanied by a 25-year-old governess, Sarah Strayer; then the children’s long-serving nurse Mary Moore and four other servants brought down from London and staying in the house.

The Rowlands kept returning to it through the 1860s for the usual stay from February into May. Alexander William is also seen sojourning there in the warmer months, between lets to various lords, knights and gentlefolk. The family biographer suggests Brighton’s “raffish” atmosphere suited his cosmopolitan outlook. He seems to have kept up the house in style – a cashbook shows in 1868 he insured the contents for £108,000 in today’s money. And while he didn’t marry again, he took a mistress and fathered four children with her.

This far from conventionally staid Victorian home life no doubt had its effect, not least on two of the daughters. Much has been written about the last-born, Henrietta, the celebrated social reformer. She married the cleric Samuel Barnett in 1873 and they worked together to alleviate poverty in London’s East End. This included founding Toynbee Hall, the first university settlement based on an idea in an article she published of places where richer students could live alongside, learn about and support the poor. Toynbee Hall continues to tackle deprivation and injustice today. Later the Barnetts, after successfully campaigning to stop Eton College developing a chunk of Hampstead Heath where they had a weekend house, also founded Hampstead Garden Suburb with the noted architects Raymond Unwin and Sir Edwyn Lutyens. Dame Henrietta lived until 1936 and is buried alongside Samuel in the churchyard of St Helen’s in Hangleton, Hove.

Alice Hart

But alongside Henrietta, her older sister Alice also ventured far beyond the path expected of a genteel Victorian woman. As well as working with the Barnetts at Toynbee Hall, she studied as an apothecary in London and Paris with utter disregard for the barriers women faced in the profession. She then campaigned successfully for their access to the laboratories of the Pharmaceutica Society of Great Britain, until then an all-male enclave.

Following that, she went in 1883 with her new husband Ernest Hart, a surgeon and the editor of the British Medical Journal, to report on health conditions in Donegal after a four-year famine there. Shocked by what they found, they established both a British fund to relieve the famine and the Donegal Industrial Fund to revive local crafts, in particular the dyeing and weaving of the traditional tweed, and for women to teach and produce Celtic embroidery. She arranged for local labourers to train in London, actively promoted the products at trade exhibitions there and in Chicago, and opened a successful shop selling them in the West End.

Her artistic upbringing came out in sharing Ernest’s love of Japanese art, combining that in her own designs for the embroidery, and in becoming a noted watercolourist. The couple later travelled extensively in Japan and then, in 1895, through Burma. That led to her writing Picturesque Burma with her brother, the Rev. William John, published in 1897. Ernest died the following year but Alice lived on until 1931.

The Rowlands seem to have given up No.19 after Alexander William died in 1869 in London, with the family from then on living slightly more modestly in general. But the flow of short-term genteel tenants continued winter and summer, through the change of freeholder in 1872 when the court allowed the trustees of those lucky newlyweds 11 years earlier to sell it for £7,200, and well beyond.

When the census was taken in April 1871 the Irish politician, writer and landowner William Pollard-Urquhart was at No.19 with his Aberdonian wife and mother-in-law, three children – separately born in Ireland, Scotland and France – and eight servants of equally mixed origins accumulated no doubt though the family’s travels. Regrettably he died there two months later aged 56, possibly one more of the many invalids for whom Brighton’s vaunted health-restoring properties failed to work. The 1881 census caught No.19 between lets with a 79-year-old caretaker, Charles Usher, formerly a gardener living in Brighton’s Temple Street and born in the Sussex village of Wartling. He was accompanied and presumably aided by his sister-in-law Martha Middleton, born in East Grinstead in 1815.

Samuel Laing by Pieter Van Havermaet

The house’s long use as furnished accommodation for the leisured visitor only came to a stop in 1890 when it was bought at auction by Samuel Laing. Born in Edinburgh in 1812 of an old Orkney family, Laing studied at Cambridge and joined the Board of Trade. At just 30 he was appointed Secretary to the Railway Department after establishing himself as an authority on the fast-growing industry. It was his suggestion that all railway companies had to run at least one train a day charging only one penny per mile so that poorer people could travel to work.

He then became a leading figure during the railways’ early-to-mid-Victorian boom-and-bust years. His links with Brighton were forged when in 1848 he was appointed chairman and managing director of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway and oversaw its largely growing success (not without opposition). Four years later he became an MP, then a Treasury Minister followed by five years as Finance Minister in India. On his return he was elected board member of the Great Eastern Railway too late to help stop it collapsing into receivership in 1867. But the day before it did, he was also re-appointed chairman of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway as it too verged on bankruptcy and he gradually rebuilt its prosperity.

By the time he and his wife of 56 years Mary, herself Orkney-born in 1819, moved into No.19 they had had 11 children, eight still living and in middle age. The following year, the census lists the couple along with seven servants. One suspects his pride in declaring his occupation as still “Chairman, Brighton railway co”, despite in his later years also re-establishing himself as long-serving MP, this time for his and Mary’s own Orkney and Shetland, and enjoying a new career as a best-selling author of books popularising modern science. And though he died at their Sydenham home in August 1897 and Mary stayed there permanently, he firmly kept his Brighton connection beyond the grave by being buried in the town’s Extramural Cemetery.

The Truth 15 November 1900. Clip from British Newspaper Archive

There perhaps couldn’t have been a greater contrast between the upright, hard-working public servant and modern industrialist and the next owner of No.19. James Frederick Townend moved into it the same month Laing died (who perhaps in ailing health had already sold to move nearer to his children in London). Through the 1880s he had built himself up as another Victorian archetype, the hard-bitten money-lender. Bradford-born in 1854, he had started his business in Leeds then opened offices under various banking-type names in Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol and eventually, with the Pall Mall Bank, in London’s Charing Cross.

His progress was also marked by an increasing number of court reports in newspapers across the country as he (usually successfully) sued or instituted bankruptcy proceedings against everyone from carters and publicans to vicars ensnared in excruciating debt arrangements. More than one judge even expressed astonishment at the eye-watering interest rates of up to 60 per cent.

Along the way in 1884 he married in Scarborough a local woman, Marian Broomhead. But her life with him back in Leeds soon became “unhappy” – others might say appalling - according to her divorce petition in 1900 on the grounds of cruelty and misconduct. It details years she had suffered of repressive and threatening behaviour, infidelity, humiliation and physical attacks. Eventually, in 1897, she had fled to her mother. He had promised to behave better, which was when they had moved together to Hove and No.19. But within two years he had gone back to his old ways. In the divorce court Townend made no defence.

Come the 1901 census he was still at No.19, declaring himself single and living on his own means, along with his twice-widowed mother Eleanor Butler from Leeds and three female servants. Two years later he took a second wife, Margaret Mitchell originally from Aberdeenshire, at Aldrington Parish Church. That marriage lasted only a year.

Evesham Standard West Midland 14 May 1904. Clip from British Newspaper Archive

Margaret won her divorce on grounds of cruelty and adultery plus £600 a year maintenance. But a year later Townend successfully got the money attachment overturned in court on a technicality which later even his own barrister said shouldn’t have been accepted by the judge. Margaret also had to pay his costs.

However, business matters were already closing in on Townend. The 1900 Moneylenders Registration Act now required them to declare what they truly did instead of hiding behind the façade of a bank. The directors of two of his businesses declared new brooms as banks with no mention of him. The London business now had to call itself the Pall Mall Advance Company.

He was personally outed in publications such as Truth Magazine, which in May 1900 referred to him as a “notorious bloodsucker” with an “insatiable rapacity as usurer”, as well as revealing his private lair at No.19. He carried on lending (and suing) for a while. But financial pressures might explain why alongside the London Gazette’s listings of bankruptcies in early 1905 there’s a short notice about No.19 being transferred to his mother. In late November she sold it to Emma St George Sabel, widow of a German paper merchant in the City of London.

Townend meanwhile seemed to have gone to ground for over a century. Until Google threw up a curious list, on the web site of the English-American Library in Nice, of expatriates buried in the local former “British Protestant” cemetery. On it was one James Frederick Townend. I then found recorded in the 1917 register of Nice town hall that he had died (“sans profession”) domiciled there on 16 August at his residence, Villa Belle Vue, 115 Promenade des Anglais. The death was declared by two of his workers, an employee and a day labourer, although the entry shows he had another wife, “Yessie Edith Williamson”. What happened to her is unclear. Perhaps this marriage had also been “unhappy”. That might explain why back in England the probate entry in October 1917 shows his effects worth £918,000 today, but a short piece in the Birmingham Post in November says he left three-quarters of it “for charitable purposes”. A vengeful snub?

In a coda to his long medley of tortuous financial dealing, a notice in the London Gazette in June 1919 reveals a solicitor still seeking any other creditors and claimants against his estate. As to Townend himself, he still lies in what became a much-derelict graveyard, alone.

British Protestant Cemetery, Nice - Townend’s final resting place

Respectability and indeed genteel philanthropy had meanwhile returned to 19 Brunswick Terrace with Mrs Sabel. Four years after her husband Ernest’s death, she appears in the 1901 census already a Hove resident, living at 16 Third Avenue with her 27-year-old daughter and a 19-year-old female servant. Local papers’ social columns also report her attendance at charitable events and other polite gatherings, and her personal donations included sending in that census year Ernest’s “extensive and exotic” collection of butterflies and beetles to the zoological museum in his native Frankfurt. Directories list her as resident at No.19 from 1908. But by 1915 she seems have returned to Third Avenue where she died in 1922.

She had sold No.19 to John Waddington two years earlier. He was born in Leeds in 1855 and trained as an engineer like his father and grandfather, then in his early twenties had headed out to Australia. But his real talent proved less to be in building things than in devising ambitious projects and then organising financial syndicates in the City of London to back them.

In Perth he met among others the local industry magnate Sir George Shenton, former President of the Legislative Council of Western Australia, and in 1879 at just 24 brought Sir George’s 23-year-old sister Evaline back to Britain where he married her in Blackheath. Settled in Kent and starting a family, he formed a group of London financiers and in 1883 presented the Governor of Western Australia with a fully financed project to build a railway running 280 miles north from Perth and opening up the area beyond. It was approved and the company was successfully listed on the London Stock Exchange a year later.

Plan of Midland Railway of Western Australia

The Midland Railway was completed in 1894, just a year after prospectors east of Perth discovered the first deposits of the fabulously rich gold fields that became known as The Golden Mile. Waddington had sold his shares in the railway and now, again with British backers, created a company to buy out the Adelaide owners of the first large-scale mine there, the Great Boulder Mine, and fund its expansion. In 1895 the company was floated on the London Stock Exchange where Waddington was hailed “King Boulder”. By 1929 it had produced more gold than any other mine in Western Australia and by 1940 almost more than any in the whole country.

Waddington remained company chairman for the rest of his life while he built interests in mining and other industries worldwide from – literally - Australia and Abyssinia to Argentina. His fortune meanwhile enabled him to engage with English life to the full. He was a founder-member of the Royal Automobile Club in 1897 and the Royal Aero Club four years later. He and Evaline moved to No.19 from Ely Grange, a small (just 13 bedrooms and a 160-acre park) country estate in Frant on the Sussex-Kent border which he’d acquired in 1898 and where they’d continued raising their three children. He had also lavishly restored the ancient but seriously delipidated family seat, Waddington Old Hall near Clitheroe (then in Yorkshire), placing an inscription over the gates: “I will raise up his ruins, I will build as in the days of old.” He was already a Justice of the Peace for both the West Riding and Sussex and had served as Sheriff for the latter in 1909. The picture shows him entertaining to luncheon at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton a large group of “representatives of the Overseas Dominions and the mayor and aldermen of Brighton” on July 13th 1911 – he (with his splendid white whiskers) is seated front and centre with the mayor in chains of office on his right. He was clearly an active and generous figure on the local county and town scene.

Representatives of the Overseas Dominions and the Mayor (Charles Thomas-Stanford) and Aldermen of Brighton, entertained at Luncheon by John Waddington, Esq., J.P. at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton, on July 13th, 1911

Credit: Brighton & Hove Museums

What precisely brought the Waddingtons to Brunswick Terrace is unclear. Their younger daughter had married into the aristocratic Tollemache family, “of Hove” as the wedding notice said, in 1914. The location offered John and Evaline the chance to host their spreading family, friends and business associates on seaside visits – alongside them, a cook and three other servants, their 12-year-old grandson Rupert John Shenton Waddington, born at Ely Grange, was also there when the 1921 census was taken. On that form, Waddington gives a London office address – 85 London Wall, in the City – and perhaps travelling up for his many board, shareholders’ and other meetings via the Brighton railway was more convenient than from the deeper countryside too. It might have also been the still much-vaunted medical benefits of the seaside that had attracted them. Recurrent health problems through his life had curtailed his international travel – he only ever returned once to Australia - and might also explain why Waddington was sent as a boy to Brighton Grammar School.

In fact, he remained busy and active for another 15 years, until he collapsed with a heart attack on Brighton seafront and died by the time he reached hospital. He was buried not in his county of birth but in Hove Cemetery South, as was Evaline in 1938. In an appreciation in The Times on his death, the Agent-General of Western Australia described the couple as “the perfect hosts” to visitors at both Brunswick Terrace and Waddington Old Hall, not least to all visitors from the Golden State down-under which had “lost the first and one of the best of London friends”.

It’s unclear what happened to his fortune. Full probate was only granted after Evaline died at the more modest address of 67 Langdale Road in Hove leaving effects of £249. No.19 had been put up for auction two years earlier. The auction booklet stored at East Sussex Record Office at The Keep near Brighton details the dimensions and features of every room including 11 bedrooms, a boudoir as well as drawing room on the first floor, and a “noble Dining Room” and Library below that. But the auctioneer records in a handwritten note on the inside cover that the house was sold by private treaty to Alice, Baroness de Chassiron, for £3,450 – a substantial fall from the £7,200 achieved by the trustees after going to Chancery in 1872, even before inflation, and another sign of Brunswick Town’s general decline in grandeur from the 1930s.

1936 Auction Booklet cover including B&W photo. From The Keep

Alice (nee Vincent) had been born 68 years earlier into a respectable London family. When she married a well-off church dignitary, John Crichton, he gave her 1 Brunswick Terrace as part of her marriage settlement. He died leaving her two sons and in 1910 she married Baron Guy de Chassiron. He was the son of a senior French diplomat and great-grandson on his mother’s side of Joachim Murat, the dashing cavalry general and brother-in-law of Napoleon I who had made him King of Naples.

From the start she seems to have been suspicious of his attitude to her as a woman of means, not letting him live with her for a year until she had made a home in Sunbury-on-Thames. Then when he moved in, she claimed an incident occurred that convinced her they couldn’t live together at all.

This all came out when 12 years later he sued for divorce on the grounds of her incapacity (presumably mental) or incompetence. The judge accepted a doctor’s statement that he’d examined her in 1914, when the Baron had previously tried and failed to divorce her for inability to consummate the marriage, and had found her “quite normal”. The judge himself suggested the only daft thing she’d done was back at the start believing the Baron’s claim in the marriage settlement of riches due from the late King Murat’s estate. He instead questioned why the Baron had taken so long to make a petition and threw it out.

Two years after, the Baroness was listed in Ladies Who’s Who calmly living between Sunbury and Belgravia and writing children’s tales and poetry. The National Portrait Gallery has several photographic plates taken in 1927 by fashionable portrait agency Lafayette, and a bronze head of her. Her most noted charitable activities perhaps started after moving to Brighton – among others she was involved in St Dunstan’s (now Blind Veterans UK), which was about to open its convalescent, care and holiday centre just outside the town in 1938, and was President of the British Sailors Society’s Brighton & Hove branch. The Streets of Brighton & Hove site lists Pier Lodge, 94 King’s Road as where she was living “from before 1930 until 1936” (the Baron had died in a car accident in 1932). However, the auctioneer’s note also suggests she was living temporarily in Welbeck Avenue when she bought No.19.

She seems to have lived well in the huge old house for the next two years. The only disturbance seems to have been the apparent theft in 1937 of a ring with which the Empress Eugenie was married to Napoleon III. The Empress had given it to the Baron’s mother, one of her bridesmaids, who had passed it on to the Baroness, her Lady-in-Waiting told the press. And she had only noticed it missing from her other jewellery when she went to show a friend. Police were, as they often say, baffled.

The Baroness left an estate worth £1.8m today when she died in September 1938, ending, as the Liverpool Post noted, another remaining link with an old Europe under Napoleon I and other emperors just across the Channel.

It was from among a much bigger and far less fortunate group of Europeans, driven by those emperors’ successors onto England’s shore, that No. 19’s new owner came. Harris Pelican bought it in April 1939. Harris had been born in 1874 near Cracow, at that time in the top left corner of the Austro-Hungarian Empire bordering Russia and Prussia. Still only a small boy, he and his family had been part of the growing wave of Jewish migrants from across the whole region seeking refuge in England from poverty and vicious persecution under all three empires’ rulers.

He might well have felt both gratitude and a pang of anxiety stemming from his past when, five months after buying No.19, he was there helping a quite possibly harassed official take down occupants’ details for the National Register, urgently needed for identity cards as the country had just declared war with Nazi Germany. (The entry for No. 19 is roughly crammed in between other odd addresses in Brunswick Square, Waterloo Street and Brunswick Street East as apparently late and hurried addendums.)

Nearly 60 years earlier the 1881 census had found Harris Valakan as was with his father Alexander (who would anglicise the surname before the next one, though why to that of a large water bird, who knows?), mother Millie and five sisters in a house in Stepney, East London. They are all listed as born in “Austria, Galicia, Cracow” but a compiler impatiently strikes out the first word and just scribbles “Poland” once at an angle in the next column.

Petticoat Lane, East London 1878 – centre of the late-Victorian Jewish clothing and tailoring trade depicted when Harris’s family arrived. Source: The Migration Museum

As a tailor Alexander would have been quickly absorbed into one of the many small (and often unpleasant) East London workshops near Petticoat Lane employing a lot of Jewish immigrants in the trade. Three of Harris’s sisters had also already gone into it and Harris would follow. But slaving in a sweatshop clearly wasn’t enough for him. By the 1901 census he describes himself as “Tailor, Shopkeeper and Employer”, living over his own premises in Hackney Road close by Shoreditch Town Hall with his wife Dora, from a Russian Jewish refugee family. They’d wed in 1894 and now already had three children (they would have nine in all). They also had a maid, 16-year-old Fanny Horsfield from Bristol.

Come the 1921 census they had moved west to the more salubrious Maida Vale with a longer-serving maid Mary Cox. His two sons were working with him and other staff in H. Pelican Limited, located even further out the east side of London on Broadway, the bustling main thoroughfare in Stratford.

This was their situation when the 1939 Register recorded Harris and Dora at No.19 along with various guests including Jack Franks, another Jewish tailor now in early retirement and possibly an ex-employee, and his wife Deborah. It’s doubtful the Pelicans engaged much with the long-established local Jewish community. The reason for buying the house seems to lie in an application he made that same September to the council to convert it into six self-contained flats, in keeping with a trend for some time along Brunswick Terrace and around the Square. However, records show that the work, though approved, was never completed. Like so many projects in wartime.

If only as perhaps occasional relief from the London Blitz, then the V1s and V2s, the house remained with the family through the war. In June 1946 Harris and Dora might well have been on one of their visits, from their home now in leafy Hampstead, when he took ill and died in Hove Hospital. His effects were £25,000, worth £833,000 today. Title to No.19 passed to Dora and their elder son Ralph, who had taken on running the business. Two years later he handed his share of No. 19 back to his mother. But she seems to have soon sold up, long before she died and was buried in 1960 next to Harris in Willesden United Synagogue Cemetery. By the early 1950s No. 19 had passed through the hands of several night club operators. It was finally properly converted into flats only after a party company bought it in 1962.

George Cheesman Senior might well have been surprised how long the house would last, as well as by the range of people who would occupy it. But then, as a man seated in what was still very much Georgian England, he could not have envisaged how much not only Brunswick Town but the whole country would be changed, economically, socially - and culturally. In 1825 Britain’s first steam railway didn’t open until two months after he signed the lease. In its colony of New South Wales, only just extending its border to what would become Western Australia, transported convicts still outnumbered free settlers and their locally born. And it would be another 20 years before mass immigration into Britain as we know it first emerged with the refugees from the Irish Potato Famine.

So, he also could not have foreseen how all the people who did ultimately pass through No.19’s doors, with their very different aspirations, endeavours and origins, would both successively embody that changing British nation and – except probably for a certain Yorkshire money lender – enrich it.

Research by Neil Fitzgerald (May 2025)

Return to Brunswick Terrace page