R-EX data Windows

Windows

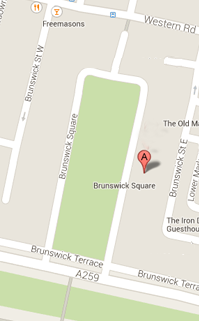

The tall drawing room windows at the front of the house are a hallmark of Regency architecture. Perhaps more than the other parts of the rooms’ design and decoration, the tall drawing room windows reflect a particular Regency preoccupation with the harmony between man and nature. The floor-to-ceiling windows ranged across the impressive bay not only brought substantial daylight into the interior but also linked it and its occupants more to the gardens and the sea and hills beyond. The depth of the bay in our drawing room is less than might be found in some Regency houses elsewhere in Brighton. This was because, among the many stringent specifications imposed by the architect Charles Busby in the Regency spirit of refined taste, was a requirement that the outside balconies on Brunswick Square and Brunswick Terrace should project no more than a certain distance from the main outside wall.

While this external wall was mainly constructed of a mix of flint, broken brick, shingle and lime mortar called bungaroush, the apertures for the windows were lined with brick before all was finished in cement. This ensured the apertures had a true line and symmetry for when the sets of windows were fitted in ready-made and -glazed with their traditional criss-cross of wooden glazing bars to support the glass panes or 'lights' as they were called in the trade.

The ‘sash window’ type used here was already the most common form in England by the beginning of the eighteenth century - though it never took off anywhere else except in Holland and North America - and to some extent remains in general use today. The name is a corruption of the French word, châssis, meaning frame. Confusingly, the ‘sashes’ are the pair of glazed panels which slide usually vertically in the window case or frame. Weights, housed inside the window frame, balance one or both of the sashes, to which they are attached by rope cords passing over pulleys fixed inside the case. The mechanism relies on the weight of the sash panel and its counter-weights being almost the same, with the weights a little heavier than the upper sash, and a little lighter than the lower sash, for easy and efficient closing.

Their snug fit made them a lot less draughty than casement windows back then which swung open on hinges at the side and (usually in those days) into the room, so also infringing on the interior space. An additional attraction of sash windows if sufficiently high was that the lower sash could be slid up to allow people to walk out onto the balcony like the one here.

The sashes and window frames were made of pine, also known as deal. It was cheap and plentiful so it was commonly used to make other fixtures as well, such as doors and skirting boards. For windows, its other advantage was that it was lighter which made the sashes easier to open and close and reduced the size of the weights needed to counterbalance them. In line with common practice among Regency decorators, Busby stipulated that the windows frames and sashes of all his Brunswick houses should then be painted indoors with a grained finish to imitate oak, which along with other expensive woods was usually only deployed in more opulent houses.

The biggest change that enabled the Regency occupants of the drawing room to fulfil their Romantic desire for more daylight inside and clearer connection with Nature outside was through improvements already being brought about by the Industrial Revolution in the un-romantic process of manufacturing glass. From 1700 ‘crown glass’ had been the superior quality product of choice. It was thinner and clearer than glass produced using other methods at the time. It was also cheaper because a tax on glass manufacture, abolished only in 1845, was based on the thickness of the product.

It involved a highly skilled process in which the glass-maker gathered molten glass on the end of a blow pipe, and then formed it into a globe by reheating, rotating and blowing. When it was the right size an iron rod called a ‘pontil’ or ‘punty’ was attached at the base of the globe to crack it from the blowpipe. The globe was then reheated and rotated again horizontally by hand on the pontil at considerable speed, causing it to be spun out into a flat disc or ‘table’, about three feet or so (about 1 metre) in diameter. These discs were placed in a kiln to strengthen and then cooled to remove the stresses built up during manufacture. They were then cut into sheets for window panes leaving only the curved edges and the circular “bull’s eye” or ‘bullion’ in the centre where the pontil had been attached.

There is a modern-day perception that this piece with its ‘bottle-bottom’ characteristic was also used widely and is a distinguishing feature of Georgian and Regency windows. But in fact at the time this part was usually discarded, although occasionally it was sold as a cheap glazing material for windows at the back of the house, such as in the kitchen and servants’ quarters, or in poorer buildings. The risk that the ‘bottle bottom’ could act as a magnifying glass for sunlight passing through it onto furnishings that might then burst into flame was another reason why it was not usually used except on the humbler sides of houses deprived of sun.

By the 1780s, crown glass was by far the most widely used and for some time remained so even after the first modern plate glass was introduced in 1832. Crown glass is distinguished by its slight green tinge, its bell-light sound when tapped, and its delicate traces of circular ‘ream’, the ripples caused by the spinning action during manufacture. But it also posed limitations. The spun table or disc tended to be thicker nearer the centre than at the edge. Window makers had to put the thicker part of each pane at the bottom to produce a better effect - although this has led to the modern myth that the glass (being "fluid like") then flowed downward in the window over the years. More important was that the maximum possible length of the glass pane had been limited to 15 inches (38 centimetres), a good bit less than half the diameter of the disc when cooled.

New processes and materials changed this. For example, coal was now widely used which gave a more consistent and cleaner heat for glass blowing and melting to provide a stronger and more evenly thin and clear product. The method of spinning the glass was also improved.

The most important result was that a bigger and more even table or disc could be produced, up to five feet (150cm) in diameter. This meant the maximum length of pane cut from it could be increased about 50 per cent, from around 15 inches (38cm) to 22 (56cm). A bigger pane meant fewer glazing bars were needed up and across the sash, the sashes could be bigger, and the frames taller without making them more cumbersome both in terms of aesthetics and of opening and closing. And so the Regency occupants of the drawing room could enjoy more light coming in and clearer views looking out through their elegant and impressive floor to ceiling windows.

The Industrial Revolution was also already leading to improvements in the processing of metals such as brass, iron and steel. Window fittings could be made lighter, stronger and finer. So the designs of visible fastenings such as catches and levers became more refined and elegant, while in the sash mechanism inside the frames the ropes started to be replaced by chains and the wooden pulleys by more durable and smoother-running metal versions.