R-EX data - house and occupants

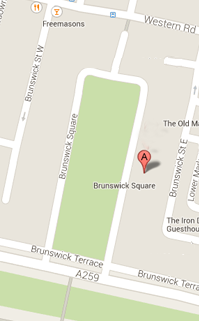

The address of The Regency Town house is 13 Brunswick Square, Hove.

The house at 13 Brunswick Square Hove is known as 'The Regency Town House'.

The house is in a terrace of adjoining houses, all designed by the same architect, C A Busby, and built in the 1820s.

The Regency Town house at 13 Brunswick Square, Hove, is being restored back to how it was when it was first built, more than 200 years ago.

The drawing rooms are on the first floor of The Regency Town House, situated at 13 Brunswick Square.

This house was built in the late 1820s by Charles Lynn and Thomas Cooper, local builders, and for the early part of the 19th century the house was rented out.

The interior of this house is described in an auction catalogue listing mansions in Brunswick Square, to be sold at the Royal York Hotel, on Wednesday 25th August 1830.

Information about the earliest residents of The Regency Town House comes from the local Parish Burial Records. The Burial Records showing William Cannon Wilmott died in this house in 1829, aged just 12 years old. We also learn that William was buried at Hanover Chapel in Brighton on 25th October and the funeral cost £1 1s 0d.

1830 saw a number of different families: Sir Thomas and Lady McMahon, William Haslewood, solicitor to Horatio Nelson, Mr Hinober, Lord and Lady Southwell, Mr Hodges, Mrs Gee and Mrs and the Misses Trowers.

In 1841 the census reveals that this house was occupied by Sir Archibald Galloway, widower and his 7 children and 5 servants. Like Sir Thomas McMahon, Archibald was a soldier in India. He married Adelaide Campbell in Bengal in Calcutta (now Kolkota) in 1815. He had 2 sons, George and James, with an unknown woman prior to his marriage. With Adelaide he fathered 12 children, 7 of whom were living with him at the time of the census in 1841. There is also intriguing but unconfirmed information that his wife Adelaide was drowned at sea off Sulawesi Tengah, Indonesia in April 1832.

After the Galloways' departure there follow various comings and goings, including Mr Goding, Mr and Mrs Rous, Sir C Sailsbury, Mr Bradish and Mr Dallas.

Between 1845 and 1848 Mary Philippa Whitton is listed in the directory as being in residence. According to the UCL Legacies of British Slavery database, Mary P Whitton counterclaimed unsuccessfully as one of the executors of her husband, William Whitton’s, will for a mortgage on the Brotherton’s Estate in St Kitts and Norton’s Valley Estate in the Virgin Islands. And although her claim was unsuccessful, she is described on the database as a mortgagee. Both estates were sugar plantations and in 1834 Brotherton's had 129 enslaved people and Norton Valley had 84. At one point William Whitton, a solicitor, managed the affairs of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The next list of people coming and going to and from this house included Rev. G. Brown, Mr Sewell, Mr George Braine, Lady Listowel, Mr John Garford.

John Gully, bare-knuckle boxer, arrived at this house In August 1848 - a man with an extremely colourful past. John Gully (1783-1863) was born in Wick, near Bath. He inherited his father’s butchery business, but in 1805 it failed and he was imprisoned for debt. While in prison he was visited by his friend Henry Pearce, a well-known prize fighter (this would have been bare knuckle fighting). A fight was arranged between them in the prison and, as a result, John’s debts were settled. Described as six feet tall with an athletic and prepossessing frame, John went on to engage in more fights, including a bout against Henry Pearce in front of the future King William IV at Hailsham, Sussex. John Gully retired from fighting in 1808, became landlord of the Plough Tavern in Carey Street, London and took to horse racing, owning several horses and winning and losing vast amounts of money. Image of a painting of the Plough Inn IMAGE Plough Inn, Carey Street, from the London Metropolitan Archives When he bought Ackworth Park near Pontefract, Yorkshire, in 1832, the Reformers of Pontefract invited their new neighbour to stand as their candidate at the general election. When John visited the town intending to decline their invitation, he was apparently so angered by comments made by the Tory opponents that he changed his mind. His candidature was successful, and he was elected MP for Pontefract from 1832 to 1837. John rarely spoke in parliament, but he served on several select committees. He declared himself an enemy of all monopolies and a friend of the poor, often voting with Radical and Irish MPs supporting reforms such as the ballot, the removal of bishops from the House of Lords, the abolition of flogging in the army and the reform of the Corn Laws. John Gully was married twice and had 12 children with each of his wives. He died in March 1863 aged 80.

In July 1850 Lord Valentia arrives at this house. Arthur Annesley, 10th Viscount Valentia (1785-1863) was an English born landowner. He inherited his title from a distant relative, George Annesley the 9th Viscount. In 1808 he married Eleanor O’Brien and they had 13 children. There was an incident while he was living at number 13 Brunswick which is worth noting. On 8th August 1850, the Brighton Gazette published a report of an inquest about a baby having been found dead in the vicinity of number 13. At seven o'clock in the morning, Charles Gillam a shoemaker from Regent Street, Brighton, had gone down the steps of this house to get some wash and saw a brown paper parcel tied with string. On opening the parcel, he saw a baby’s ear and went to get George Breach the inspector of police. Breach untied the parcel and discovered the body of a baby boy. When questioned William Colly, Lord Valentia’s footman said that he had locked the gate at 11 o'clock the previous evening and had not seen a parcel. The inspector could see no signs of violence and took the baby to James Oldham, a surgeon living in Norfolk Square. The Gazette details Oldham’s examination and as with many newspapers of the time they make grim reading. It appeared that the baby was born alive as it had taken breath, but the cause of death could not be ascertained. Other servants from the house were questioned at the inquest and the jury returned a verdict of “found dead”. Unfortunately, the report appears to leave many unanswered questions. Whose baby was it? Why leave him wrapped up in a package at number 13 Brunswick Square? Are there any connections to Lord Valentia or his servants? We will never know. Lord Valentia departed Brighton in September 1850.

For the remainder of 1850 a few people came and went, Mr and Mrs Jackson, Mrs Frere May and Lord Milford. In the 1851 census the house is listed as uninhabited.

Then, between September 1851 and 1855, James Neil, Mr Levision, Mrs Royd, Mr Blake, Mr Weir and Mr Goldsmid all resided in the house at some point. Soon after, two joyful events go some way to counter the tragedy recorded during Lord Valentia’s occupation of this house.

Moses Levy and his family arrive in September 1855 and the Morning Chronicle reports that on the 3rd October, “the wife of Moses Levy has given birth to a daughter at number 13 Brunswick Square".

Next, on the 11th March 1856, the Reverend Henry Landon Maud’s wife Amelia gave birth to a daughter Constance Elizabeth. Constance divided her adult life between France and England and became a successful author and was part of the women’s suffrage movement. One of her best-known novels based on real events was No Surrender published in 1911. It was republished in 2011 to mark the 100th anniversary of its original publication. Emily Davison, the suffragette who famously threw herself under the King’s horse in 1913, described the book as containing the very spirit of the Women’s Movement. No Surrender is considered an important contribution to the advance of votes for women.

In the years which followed this house was largely inhabited by the same people, from 1857 to 1891 the Kepps were in residence and later until 1920 the Furners. 1856 to 1891 Newspaper cutting of an advert fro a lady's maid This intriguing advertisement was in the Brighton Gazette of 1856, but who was she working for and why was she looking for a change of job? The directory of 1856 lists a Mrs Powell at 13 Brunswick Square but tracking down either Adeline or Mrs Powell has not, so far, been possible. How is a 1821 newspaper report about St Paul’s Cathedral connected to this house? Read on.

John Kepp, a coppersmith and brazier, lived at 42 Chandos Street, Covent Garden, with his wife Phoebe (Lloyd) who he married at St Martin-in-the-Fields in 1784. The couple had four children Richard (1788-1878), Edward (1791-1875), Julia (1796-1865) and Phoebe (1798-1891). John died in 1818 leaving the coppersmith business to Richard who, with Edward, continued to run it as R & E Kepp until 1855, when they sold it to Benham & Froud. The business was a thriving concern, from John Kepp’s premises at number 40 Chandos Street the brothers had expanded into 41 and 42. It was Richard and sisters Julia and Phoebe who had the greatest association with this house, although Edward was, no doubt, a visitor. There is no evidence that Richard, Edward or Julia married. In fact, Richard and Julia lived together either in their London home at 15 Sussex Place, Regents Park, or at this house. The Brighton Gazette between 1857 until 1865 chronicles their comings and goings. For example, on 4th October 1860, the Gazette heralds Julia and Richards’s arrival for the winter and the same newspaper on 14th March 1861 reports their departure for the summer. Several dinner parties are also recorded in the press but, sadly, without a guest list. The pattern of Brighton for the winter and London for the summer continued until 1865, when Julia died at the age of 69, in this house. Newspaper cutting featuring the death of Miss Julia Kepp Brighton Gazette, 30th November 1865 The local Brighton directories then list Richard Kepp as the householder of this house between 1859 and 1869, after that he is listed alongside Mrs Wardell (sister Phoebe). Phoebe was the only sibling who married, albeit briefly. She was wedded to John Wardle in 1837 in Marylebone. She was 39 and he was 51. They were married for 6 short years until he died of apoplexy (probably a stroke) at Gerrard’s Cross. They had no children. So where was Edward Kepp? He was still in close association with the family. In the 1861 census he was living at 104 Marylebone Road and sister Phoebe was at number 106. Edward died in 1875 followed 3 years later in 1878 by Richard. Phoebe continued the pattern of living at 15 Sussex Place, London and this house for the rest of her long life. She died in 1891 at the London house at the age of 93. In her will she left in the region of £156,000, about 25 million pounds in today’s money. So a close-knit childless family with a long association to The Regency Town House were gone and where the money ended up is the subject of further research.

The next time you are in the city pause to look atop St Paul’s at the magnificent orb and cross and marvel at the intriguing Kepp connections, or maybe take a stroll to Sussex Place and imagine Richard and Julia preparing for their journey to Brighton for the winter months.

The 1891 census has two of the Kepp's servants living at the house: housekeeper, Mary Anne Agnew aged 53, and housemaid, Christine Matheson aged 34. Mary Anne’s husband, Edward Agnew, was at the Kepp’s London home at 15 Sussex Place working as a butler. He had been with the family off and on since 1861 when, at 18 years old, he was working for them as a page. The pair married in 1874 at Hurstpierpoint, Mary Anne's birthplace. After Phoebe Wardell’s death, Edward and Mary Anne moved to Lancing and he took up poultry keeping. Mary Anne died in 1904 aged 66 and in 1905 Edward married Ellen Camfield, who also worked for the Kepps. 1892 to 1920.

In 1892 the Furners moved into number 13. Willoughby Furner (1848-1920) was a doctor like his father, Edmund Joseph Furner. The family lived for several years in Kings Road, Brighton. However, in the 1891 census Edmund was living with his wife Arabella and daughter May O’Brien Furner at 47 Brunswick Square, Willoughby and his wife Ada were at 2 Brunswick Place. Image of Doctor Willoughby Fowler Dr Willoughby Furner Willoughby had succeeded to his father’s practice in 1876 at the age of 28. He had trained at St Barthomew’s Hospital and become a demonstrator of anatomy and operative surgery. On taking over his father’s practice he was appointed as assistant surgeon to the Royal Sussex County Hospital as well as to the Blind Asylum and the 1st Sussex Rifle volunteers. Willoughby Furner married Ada Skipper (1851-1912) in 1888 in Kensington, he was 40 and she was 37. Ada’s father Charles Skipper was a stationer and printer who printed bank notes for the Bank of England and in 1834 published a response to the Poor Law. In 1892 Willoughby and Ada moved into number 13 and played a large part in the life of Brighton. There are frequent mentions of them in the local newspapers. For example the Brighton Gazette reports on 15th January 1903 a ”brilliant gathering at the Royal Pavillion“ with over 500 guests including the Furners. Willoughby also attended to Eliabeth Gore aged 95 when she was dying. Elizaberth lived at number 26 Brunswick Square and had resided there all her long life. Elizabeth and her family were a large part of life in the town. More about the Gore family in the future. Ada Furner died in June 1912 and was buried in Brighton Cemetery. During WW1 Willoughby was a medical officer at the Auxiliary Hospital at 6 Third Avenue. The house was loaned to the Red Cross by Sir Cavendish and Lady Boyle for the duration of the war and refurbished to meet the demands of caring for soldiers wounded on the western front. 1,431 patients were treated at Third Avenue over the course of the war. The Red Cross opened over 3,000 such hospitals across the country to meet the demand of the expected large number of casualties from the front. In 1920 Willoughby died at this house aged 73 after a long illness, he had received an OBE for the work he had done in WW1 and was buried with Ada in the Brighton Cemetery. This personal obituary seems to sum up how he was seen by someone who knew him well. Newspaper cutting of the obituary of the late Doctor Willoughby Furner The late Willoughby Furner 1920 obituary And so a snapshot into the history of some of the people who lived at this house Square between 1829 and 1920 draws to a close.

The first part of this house history ended with the death of Dr Willoughby Furner. His place was soon taken by another doctor, John Richard Griffith. Including John’s wife Maud (also a doctor) and their three children, the Griffiths lived in the house from 1921 to 1949.

The early twentieth century was a time when Brunswick Square was starting to change. Large detached family homes in Hove, complete with gardens, were becoming more popular. The houses in Brunswick Square no longer appealed to such families and many were being formally converted into flats or were otherwise lived in by unrelated couples, individuals and families. this house was no exception and the Griffiths did not have the house entirely to themselves. The basement became a separate residence, initially lived in by Reginald Barron and his family (we will come back to them later).

After the basement was vacated in the late 1940s, we do not know exactly how the living space was divided until much later, when numbered flats are identified in the official records. Given that there were numerous residents over the years, some of whom stayed only for a short time and others where it was difficult to find out much about them, this is not a comprehensive history.

Returning to John Griffith, he was born in November 1887 and spent his early years living locally, at 15 Buckingham Place and 59 Montpelier Road. He had two younger brothers, Henry (b. 1891) and William (b. 1897) and a younger sister Sarah. William died in action onboard HMS Indefatigable in the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Henry died in 1917, apparently in a flying accident.

John was educated at Brighton College, Christ's College Cambridge and St Bartholomew's Hospital in London. He also saw action during the First World War as a surgical specialist in the Royal Army Medical Corps. John’s wife Elsie Maud (née Visick, b. 1894) preferred to use her middle name, and they married in 1921. Maud followed a family tradition as both her father (Charles Hedley Clarence Visick, who died in December 1939 aged 84) and brother (Arthur) were doctors. Charles was visiting his daughter and son-in-law in their new home at the time of the 1921 census. The Griffiths also had two servants listed in the census, Rose Terry and Maude Gertrude Sommers. John and Maud had three children whilst living in the house: son Richard Henry (b. April 1923), daughter Nancy Maud (b.1925) and son Adrian Nicholas (b.1928).

Richard followed in his parents’ footsteps, became a doctor and joined the medical register in 1947. By 1955 he was living in Kidderminster. Later, he emigrated to Australia where he lived and worked in a different Brighton (in Victoria) for some time. He travelled to Melbourne (via Sydney) in 1957 with his wife Denise (b. 1921, née van der Meer) and son Michael (b. 1949). He and Denise had married at Cuckfield in 1948. He died in Australia in 2002, after a long period of ill-health.

Nancy married Harry Edward Gardam in 1948 in Hove and their daughter Sarah was born in 1964, in Bromley Kent. Harry had been a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy. They also had a son, Jonathan, born in December 1954 Nancy died in 1980 (age 54). We understand that she had worked in radiography, which might partly explain her relatively young age when she died. We also know that her mother Maud had met Marie Curie’s daughter when she worked at the Marie Curie Hospital in London: perhaps this inspired Nancy to work in radiography. When she died, Nancy was living at Whydown Farm, Bexhill on Sea and left just over £125,000 (about £490,000 today).

Adrian, too, followed in his parents’ footsteps, especially his father’s as he studied at Cambridge and St Barts. The 1955 medical register records him living at the family home at Bee Houses, Bolney. In 1947, when a student, he travelled by ship to St John’s, Newfoundland. In 1959 he visited North America again, this time going to New York by ship, on a scholarship from the Medical Research Council. It was while he was working in Chicago that he first became seriously ill. In 1961, aged 33, Adrian married opera singer Catherine Julia Wilson, at Northallerton, Yorkshire, but tragically was dead five months later (in Islington). It seems that he had never regained his health. He left just over £17,000 (about £350,000 today).

Shortly after Adrian’s birth, other individuals start being recorded at this house on the voters list. It is unclear what the living arrangements were at that time, so we do not know if these people were lodgers (say) or had their own part of the house. For example, in the 1929 voters list we see Winifred Carr, Constance Chadwell and Kate Perris. Nothing is known about any of them.

In the 1939 Electoral Register, John and Maud Griffith are living at this house. They also have one servant, Ida Frehner, a cook, born in Switzerland on 4th June 1920. Unfortunately, nothing more is known of Ida.

Maud Griffith was dedicated to the treatment of women and children and, with her husband, was an active member of the Brighton & Sussex Medico-Chirurgical Society (chirurgical is an old-fashioned word for surgical). John became president of the Society and, whilst Maud never did, she did hold both Honorary Secretary posts (Financial Secretary and Literary Secretary). One of the main activities of the society was to present medical papers to fellow members at regular meetings. For example, in 1936 Maud presented a paper to the society on “Carcinoma of the Cervix”. In it, she bemoaned the fact that (mostly male) doctors did not take post-menopausal bleeding seriously enough. Such bleeding could be a sign of cancer, which could be treated with radiation. She also presented a paper on “Woman and her disabilities” in 1944. It would be wonderful to hear Maud’s views on this subject, but the paper has not yet been found.

She is closely associated with the New Sussex Hospital for Women and Children, at Windlesham House, Windlesham Road, which was “officered by women doctors”. As we will see later, many women welcomed (or would have, given the option) the opportunity to be treated by another woman. Windlesham House was built in 1843-44 as a school and opened on the site in 1846. Its transformation into a hospital was largely due to the efforts of Louisa Martindale, Elizabeth Robins and Octavia Wilberforce, who were instrumental in raising funds to buy Windlesham House, it being the most suitable building available at the time.

The New Sussex Hospital opened in 1921 under the direction of Dr Louisa Martindale, daughter of the Louisa mentioned above. If you are local to Brighton & Hove you will be familiar with this name - the new wing of the Royal Sussex Hospital is named after her.

Maud was both a physician and a surgeon. She lived in the house from 1921 to 1949 and was living at Flat 1, 17 Wilbury Road, Hove when she died “peacefully in hospital” in March 1967.

Richard Griffith also worked with children, in his case at the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Sick Children (which was then in Dyke Road) where he was a surgeon. He also worked at the Royal Sussex Hospital as a physician. Like Maud, he was a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. Richard was a general surgeon and a paediatric surgeon, particularly interested in the repair of hare lip and cleft palate, which sufferers are usually born with (rather than develop in later life).

Some architectural changes inside this house, together with the discovery of children’s toys under the floorboards in that part of the house, led to the idea that part of the house had at some time been used as a children’s hospital. However, there are no formal records of a hospital or nursing home at this address. It is more likely that the space was used for prehabilitation i.e. improving the physical condition of children before they had surgery. We know that Richard was interested in prehabilitation because his presidential address to the Medico-Chirurgical Society in 1943 was called “The Preparation of Patients for Operation, their after-treatment and Comfort”. In it, he mentions how important it is for patients to be in good physical condition before an operation. Richard died of a cerebral haemorrhage on 14th October 1956, by which time the family were living at Bee Houses, Bolney, Sussex. He left just over £31,000 (around £740,000 now).

Having spent so much time with the Griffiths, let us now return to the residents of the basement at number 13 in 1921, the Barrons. As previously mentioned, the head of the household was Reginald Cardwell Barron. He was born in 1882 in Farnworth, near Bolton, Lancashire. In 1906 he married Ada Naomi Kippax at St Johns, Newington, Surrey. His profession is given as a photographer, the same as his father William. Ada is described as a Chemical Assistant; perhaps she was working in the dark room.

In 1911 Reginald, Ada and their daughters Phyllis aged 4 and Rita aged 7 months are living at 14 Eastern Road, Clapham Junction. He is still a photographer. Like John Griffith, Reginald took part in the First World War, in his case as a driver with the Royal Field Artillery. According to the Electoral Register, by 1918 Reginald and Ada are both registered to vote and are living at 4 Little Western Street, Brighton. They are still there in 1919 although obviously by the time of the 1921 census Reginald and his family have moved to 13 Brunswick Square. He is listed as being Regular Army Late at Present Out of Work. The couple also now have a third daughter Ruby, born in 1914.

The Barrons continued to live at this house until 1923. In the 1939 register Reginald is recorded as working as a Builders Decorator, now living in Southend with Ada and daughter Rita. He remains in Southend and dies in 1947 aged 65. Ada dies in 1972 aged 88, also in Southend. Lodging with the Barrons in 1921 were Mozart Allan and Margaret Stuart Allan. Mozart was born in 1889 in Glasgow and baptised Ebenezer James Mozart, although he is usually referred to as Mozart. He was from a musical family: his father William H was a musician/teacher as were his brothers Haydn and William. Margaret Stuart Allan was born in 1886, also in Glasgow.

Rather unexpectedly there are a surprising number of Mozart Allans, and working out which one was living at this house in 1921 was rather tricky. In the 1911 census, aged 21, Mozart is a visitor in Hulme, Manchester and describes himself rather grandly as a Professor of Music. Also present are George and Dorothy Payne, Music Hall Artistes. In 1916 Mozart enlisted in the Royal Marines Band. In the 1921 census at number 13 he is described as a violin/cellist working for the West Pier Orchestra and Margaret is a Writer (own account), probably meaning she is self-employed. In the 1920s the West Pier was hugely popular, with up to 2 million visitors every year. The concert hall there supported a full-time orchestra. There are also numerous mentions of Mozart Allan as conductor and solo cellist of the Municipal Orchestra in the Hastings and St Leonards Observer between 1933 and 1936.

In 1939 Mozart and Margaret are living in Weston-super-Mare. He is a musical director and Margaret (although possibly a different Margaret from the one on the 1921 census as this one was born in 1879) is doing unpaid domestic duties. There is no trace of Mozart having married any Margarets (or anyone else) and it is likely that he died in 1957 while living in Hornsey.

Jesse Austin and his wife Elsie moved into the basement around 1927. We understand that they lived in the basement in exchange for maintaining the furnaces which fired the central heating and hot water for this house. Jesse was born in Hove in May 1881. His father (also called Jesse) was a gardener, his mother was called Lucy and they lived at 19 Connaught Terrace. Jesse joined the Royal Navy in January 1898, becoming full-time in 1899. His Naval Record says he was age 12 at the time he joined, but this is obviously wrong. His occupation was given as a butcher. Naval Records are wonderful because they give a physical description of the individual. So, we know that Jesse was 5 ft 6 ins tall with brown hair and grey eyes. By the time he was age 18, he was 5 ft 8 ins. At the time of the 1901 census, he is an Able Seaman on board ship in the Royal Navy at Gibraltar. His record shows a good or very good character throughout and he, too, served in the First World War. He was demobbed in February 1919.

Jesse married Elsie Unsted on 18 March 1919; she was 10 years younger than him. In the 1911 census Elsie (aged 20) is working for Sir Charles William Cayzer, a shipowner, his wife Annie and their 3 young daughters. There are a total of 7 servants present at the family’s home at 22 Lewes Crescent, Brighton and Elsie is an Under Nurse. At the time of their marriage Jesse and Elsie lived in Falmer and they married there. By this time Jesse was a parkkeeper. His father’s profession is now given as a nursery man; Elsie’s father William was a smallholder. William also worked variously as a gardener, farmer and coal merchant. In the 1921 census the pair are living at 14 Brunswick Road, Hove. Jesse is a gardener working for the Corporation of Hove based at St Ann’s Well Gardens. Elsie is described as having Home Duties. As we know, they later moved to number 13 Brunswick Square, where they stayed for many years. In the 1939 register Jesse is a gardener. We understand that he looked after the central garden in Brunswick Square. Amongst other things, he cultivated beds of wallflowers, primroses and snapdragons and arranged an annual bonfire for Guy Fawkes Night (5th November). Jesse also put his green fingers to use at home in the basement, where he illicitly grew tobacco plants on the windowsills! The Griffith children were sworn to secrecy because this was obviously illegal and Jesse would have been in serious trouble with the Excise officers if he had been discovered. Elsie died in Brighton in 1943 aged 52 and Jesse died in Hove on 13 March 1952. They are both buried at Falmer. Jesse last appears on the voters list at number 13 in 1948. After that, we understand the basement was empty until 1962. It was then briefly occupied by James and Gwendoline Massey but after they left in 1964 it became uninhabited.

We now reach a period of the house’s history where we have no idea who lived there (or even if anyone did). From 1951 to 1964 there are no entries in the street directories and in addition there is no available voter information from 1949 to 1961. However, there are three planning applications over the period 1954 – 1959 and these reveal a continued link between the house and the medical profession.

The first planning application, in 1954, was made on behalf of Dr Oreste Sinanide. From the plans we can see that the house had already been formally divided into a number of separate living spaces. There is no evidence that Dr Sinanide ever lived in this house. However, he and his common-law wife Florence did live in Paynesfield in 1952/3. Florence had changed her surname to Sinanide in October 1949. At the time Oreste was still married to his wife Maria, who he married in London in 1915. However, she was an invalid and they were evidently estranged. She died in France in 1953.

Dr Sinanide was a colourful character. He had medical qualifications from universities in Athens and Paris and received his British naturalisation certificate in 1922. He specialised in non-surgical beauty treatments and advertised his practice for many years in The Tatler magazine. His key advertising slogan was “Youthfulness is a social necessity – not a luxury”. This slogan took other similar forms, including with the word “youthfulness” replaced by “beauty”. This eventually led to a legal case in 1928 when Dr Sinanide sued Mr Charles Francis Brown, a plastic and cosmetic surgeon who traded as La Maison Kosmeo, for infringement of copyright. Sinanide claimed to have invented the phrase “a social necessity not a luxury” and claimed copyright of it. It seems that he won the original case, but Brown appealed. The appeal was successful i.e., Sinanide had no copyright over the phrase. We will leave this case with a quote from one of the judges, Lord Justice Scrutton: “The dispute was one between two beauty specialists … who traded upon the knowledge that there were people who had plenty of money and no brains and who were prepared to spend that money in improving the faces that Providence had given them”. Oreste died in Valencia in 1958.

The second and third planning applications were made in late 1958 and early 1959 on behalf of Dr Arthur A Spiro, yet another medical practitioner. Like Maud Griffith, Arthur evidently preferred to go by his middle name as his given name was Abraham Arthur Spiro. He was born in Dublin in 1902 but, by 1911, the family had moved to north Manchester. The census shows Arthur’s father David to be a Jewish linen merchant who had been born in Russia but was now naturalised. Arthur lived with the rest of his family: mother Sara (who was also from Russia) and nine siblings. The census also tells us that a further sibling had died. By the time of the 1939 register Arthur was medically qualified and living in Hammersmith, London.

There is no evidence that he lived at number 13, but Arthur lived for a time in Worthing. He died in 1963 leaving a widow, Betty. His estate was worth just over £22,000 (around £390,000 today).

From 1961 onwards, this house is inhabited again. By this stage, the basement is no longer regularly inhabited but the upper floors of the house hold numerous residents - perhaps one individual or family per floor. However, this is not to say that they were representative of the impoverished students and “little old ladies” of popular stereotype.

In 1960 Evelyn Emily Ray Warne, born 22 January 1881 is living in this house with her son Herbert Bernard Ray Warne, born 29 March 1926. Ray was Evelyn’s maiden name. She was married in 1912 but she and her husband were subsequently divorced in 1918. The marriage was declared null and void on the grounds of his inability to consummate it. The language used in the divorce proceedings looks quite demeaning to modern eyes and it must have been a terrible experience for them both. It also cost £70 (over £2,000 today) just to instigate the divorce. In addition, the papers were then closed for 100 years. However, Evelyn was undeterred and later married Herbert Henry Warne, in Canada, in 1925. He was born in 1879 in Alverstoke, Hants and died in 1954 (living at Orchard Avenue, Hove, leaving about £1,000 or £24,000 in today’s money). And they of course had a son, Herbert. The family had already moved back to the UK by the time of the 1939 register: they were living in Shoreham-by-Sea at the time. Evelyn had been a teacher and was evidently a determined woman (we have already seen evidence of that in the divorce case). There is a story in the Worthing Gazette in 1915 that she declined to accept a teaching post for less than £100pa salary. She had been offered £90 but turned it down. Then, “in view of her past experience” it was agreed to pay her the £100pa. She died at the New Sussex Hospital on 26 September 1960, her address was flat 5, 13 Brunswick Square. Despite this, she appears on the electoral register from 1961 to 1963! Herbert lived in this house until 1966. Not much is known about his life, but he seemed to remain in the area and died in Hove in September 2007.

Also arriving in the house around the same time as Evelyn and Herbert is Lady Phyllis Floud. She is living in this house with her husband Sir Francis Lewis Castle Floud. He has the very unusual distinction of receiving three different knighthoods for his work in public service. His obituary in The Times is headlined “Distinguished civil servant”, which usefully sums up his life and career. His work spanned periods in the Ministry of Labour, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries and the Board of Customs and Excise. He was also a British High Commissioner in Canada and worked in India as chairman of the Bengal Land Revenue Commission. Unsurprisingly, his distinguished career was recognised by having several portraits in The National Portrait Gallery. Born in 1875, his relatively modest family circumstances meant that he was unable to go to university nor was he able to pursue his wish for a legal career. Hence his decision to join the Civil Service. Given the broad extent of his career success, it comes as no surprise that he also studied law in his spare time and was called to the Bar in 1904. Francis and Phyllis were married in 1909, when she was aged 23. They had two sons, Peter and Bernard, and a daughter called Phyllis (who went by the name of “Mollie” and was Peter’s twin). Mollie married Peter du Sautoy, who became chairman of publishers Faber and Faber. You might have heard of their grandson Marcus du Sautoy, the mathematician. Bernard had a more chequered life. He was the Labour MP for Acton from 1964 to 1967 but was accused of working for the KGB. He took his own life aged 52, only days after he was interviewed by MI5 about the alleged links to the KGB.

Phyllis Allen Floud (née Ford) was born in Hampstead; her father was a colonel (and an OBE). There is a first-hand account of her early years because she wrote a memoir during the 1940s. This was discovered later by Cynthia Floud, the wife of one of her grandsons. Cynthia edited the work and it was published in 2018 as “A Dysfunctional Hampstead Childhood 1886-1911”. Cynthia also gave a talk about it to Camden History Society. This is how the talk was described: “Phyllis was born in Hampstead in 1886 into a family whose income did not match their self-perception of their position in society. Looking back over her childhood from the distance of middle age, she recounts, in unusual detail and with a critical eye, the customs and lifestyle of the upper middle classes in her youth. She does not shy away from indecent exposure, sexual coercion and the constraints of courtship; she turns her sardonic gaze onto decor, dance cards and doctoring; she moves from the social rules of women’s cycling to riding on horse buses.” A local newspaper added some further details: “One of the most fascinating aspects she discusses is how women dealt with doctors. They just didn't have the vocabulary to talk about what was wrong with them. One of the more striking examples - Phyllis had appendicitis, but she was only able to identify it when it was in the papers because Edward VII had it. Then, when giving birth, they just didn't listen to her when she said there was still pain after the first baby was born. And of course she had twins.” What a pity that Phyllis did not have access to a doctor like Maud Griffith.

Phyllis Floud was a woman apparently ahead of her time. An obituary in The Times records that she took an early morning swim well into her eighties. She was also a painter and had her work exhibited locally. Phyllis was living at Grosvenor House, Kings Road, Brighton when she died in 1976. She lived in this house from 1961 to 1975. Her husband had died in 1965.

Kathleen Edith Hartridge moved into this house in 1966. She was born in October 1885 to Sir James Fortescue Flannery MP and Lady Edith Flannery of Wethersfield Manor, Essex. Her husband was Charles Eric Addington Hartridge, born in November 1882 and who died in 1960 after a long illness, leaving just over £127,000 (over £2.5 million today). Their marriage had to be re-arranged due to “recent family bereavement” and took place “quietly at the Royal Chapel of the Savoy” on 24th April 1913. The couple had three children: Charles Anthony (b. 1916), Rosemary (b. 1918) and Adrienne (b. 1922). In the 1939 Register they are all living at Findon Place, near Worthing. Charles is described as a barrister at law. They had moved to Findon in 1932 and took over the ownership of Findon Place following the death of the previous owner, Colonel Margesson. A newspaper report from February 1966 says that Kathleen is the owner of Findon Place but lives in Hove. Reports from later the same year explain that the new owner of Findon Place, Mr Robert K Middlemas, had applied to Worthing Rural Council for a grant or loan towards the cost of repairs and restoration of the house. The cost was estimated to be almost £3,000 (around £53,000 today). Kathleen lived at this house until 1969. She died on 13th September 1974, leaving just over £48,000 (over £350,000 today). Her address at death is given as St Raphael’s, a care home in Danehill, Haywards Heath.

We now turn to a couple, Daisy and Edward Lisher, who also moved into this house in 1966. Their lives were quite different from the Flouds and Griffiths. As we have already seen, if you are doing social history research it’s always good news if someone has a naval record because there is always a physical description. We therefore know that Edward Alfred Lisher, b. 1896 in Worthing, was 5 ft 4½ ins tall with brown eyes, brown hair and a fresh complexion. He had a scar on his right thigh from a bullet wound he received in May 1915, whilst fighting in the Dardanelles during the war. He married Daisy Page, b. 1898 in Rotherfield, in 1920. It took a while to be certain that this was the right Daisy, because Edward uses the middle name “Valentine” on their marriage certificate! This is the only time Valentine is used – perhaps Edward was simply romantic. They had lived in a succession of grand properties. For example, in 1929 and 1930 they are at 16 Chester Terrace (this is one of the neo-classical terraces in Regent's Park, London, designed by John Nash and built in 1825). In the 1946 and 1947 electoral register, they are at Northease Lodge, Rodmell. And from 1953 to 1962 they were at Findon Place, Sussex. Because there are no published censuses for these periods it was not obvious what their relationship was to these grand houses but, eventually, the 1939 Electoral Register came to the rescue. At that time, they are at Pear Tree Cottage, Bledington, Cotswolds. Edward is a chauffeur (domestic) and Daisy is doing paid domestic duties, so they were servants. It is intriguing that Edward and Daisy were, in 1966, now living in the same house as Lady Floud and their old boss, Kathleen Hartridge. We know that the old social hierarchies were starting to break down in the 1960s and perhaps this is an example of that. Kathleen and the Lishers first appear on the house records at the same time but the exact relationship between them and the timing of their move into this house is unclear. Edward Lisher died in 1969 but Daisy continued to live at number 13 until 1975. She died in 1984.

Diana Joll also moved into this house house in 1966. We will come back to her later because she was the final resident of number 13.

We now turn to Geoffrey Kershaw Bennison, who moved into this house in 1973. Geoffrey, b. 1921 in Ashton-under-Lyne, was a well-known interior designer. He studied at the Slade School of Art and apparently excelled as a painter and stage designer. However, he contracted tuberculosis and spent eight years in various sanatoriums in England and Switzerland. In the early 1950s he opened a stall in Portobello Road antique market and it is here that his career takes off. Geoffrey took up decorating in the early 1960s, when a friend asked him to design London’s first sophisticated Chinese restaurant, the Lotus House. Among its fashionable regulars were the model Jean Shrimpton and her boyfriend, actor, Terence Stamp, who hired Bennison to furnish his Mayfair flat. Stamp was so pleased with the results that he called upon Bennison again when he moved to a spectacular set of rooms at Albany, one of London’s smartest addresses at the time. There is a wonderful description of Geoffrey’s homes online: “For many years Bennison's own exquisitely arranged apartment in London was an unlikely eyrie high above Piccadilly Circus, where he had assembled a perfect mélange of quirky and beautiful objects gathered over many years of dealing. His flat in Brighton was also a place of curiously raffish charm. Then, just a few years before his death in 1984, he moved to the top floor ("the nursery," he called it) of a grand house on Audley Square.” As far as we can tell, number 13 was his only residence in the Brighton area, so the flat referred to was probably in the house. One of Geoffrey’s design mantras was “always put something mad on top of something very good, or something very good on top of something mad”. He left the house in 1975 and died in 1984, leaving nearly £465,000 (around £1.3m today).

It is now time to go back to 1966 when Diana Joll moved into this house but it does bring us almost up to the present day because, as mentioned previously, she was the last person to live in number 13. Like Phyllis Floud, Diana was born in Hampstead, although she was born later, in 1927. Her obituary was published in The Guardian on 31 December 2019, and it seems a fitting tribute to her to include some extracts here: “Diana Joll, who has died aged 92, had a successful career in social work, beginning in 1949 as house mother in a children’s home and ending in 1987 as a senior psychiatric social worker for Brighton and Hove council. In parallel, she developed a passion for the art of the silhouette, collecting more than 700 works and achieving national recognition for her expertise in the subject. Diana was strongly influenced by her father, Teddy Joll, an artistically-minded civil servant who had met her mother, Molly (nee McClean), in the 1920s. They divorced when Diana was five, and a few years later Teddy married Mary Brunner, who had been a nursery school teacher and was a calming influence in Diana’s life. Diana attended Frensham Heights boarding school in Surrey, then took a degree in social administration at Manchester University, graduating in 1949. She showed bravery at her first job, as house mother in a children’s home in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, challenging the repressive matron who ran the place. In 1951 she moved to London to work across the capital for the Invalid Children’s Aid Association and then the Family Welfare Association, which was based at the Paddington Citizens Advice Bureau. She then worked as a child care officer with Hampshire council’s children’s department, based in Winchester (1953-58). In 1958 she took a mental health course at the London School of Economics and the following year began work as a psychiatric social worker at St Francis Hospital in Haywards Heath, Sussex. The Mental Health Act (1959) had proposed changing the emphasis of care to rehabilitation in the community, and Diana was instrumental in effecting the reforms in Sussex; by 1963 she was head of a nine-strong team of social workers. She stayed in that role, with Brighton & Hove Council, until her retirement in 1987, after which she continued to help former clients on a voluntary basis through support groups in Brighton & Hove. The diligence she applied to her career was matched by her devotion to the art of the silhouette, which had begun on her move to Brighton. Her collection, which is the basis of the Profiles of the Past website, was enhanced by its setting in her flat in this house. With the help of members of the Silhouette Collectors Club, of which she was secretary from the 1980s until her death, she was able to entrust care of the works to the house”.