Nick - house tour transcript raw

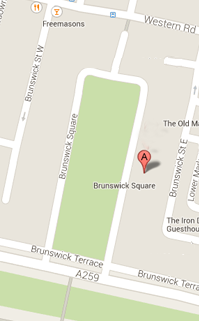

Welcome to The Regency Town House, at No.13 Brunswick Square, Hove. A developing a small heritage centre for the city, one that’s focused specifically on Brighton and Hove’s urban architectural legacy - the fabulous terraced architecture forming the Squares, Crescents and Parades for which Brighton became famous some 200 years ago. I’m sure most of you are familiar with the magnificent Royal Pavilion in the centre of town; a royal palace where the focus is very much on George and those immediately around him in the court circle. Here, in contrast, we are interested in what might be termed the lives and homes of ‘ordinary people’, within which turn of phrase I’m including: The rich, powerful, characters living upstairs in houses such as this, some of whom certainly interacted with those in the Royal Pavilion, The rapidly developing middle classes of the period, such as the architects designing new homes and the lawyers negotiating property sales. And, those at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum, such as the artisans working in the building industry, the servants employed in homes like this, and the proverbial butcher, baker and candlestick maker. Unlike the Royal Pavilion, we don’t have millions of pounds to spend on our renovation program, so work here depends heavily on volunteered time and effort. Still, each year, we move a little closer to our objective of presenting a fully repaired house, which in time will offer some rooms that are finished and furnished to original specification and others where visitors can explore a mix of educational resources about 18th and 19th Century history.

First, with the aid of a picture pack, we’re going to take a look at the transformation of Brighton from a coastal fishing town to a fabulous and fashionable resort. Second, by visiting some of the rooms here in No.13, we’re going to explore how property in Regency Brighton was built and decorated and how those in fashionable society lived upstairs in houses such as this. Third, we’re going to contrast the lives of those upstairs with the people working downstairs on their behalf, taking a look at the domestic offices in our other property at No.10 Brunswick Square.

Before we begin our tour though, let me briefly address the term ‘Regency’. There are two different definitions and this sometimes causes confusion. In a strictly political sense, the Regency is a short period, starting in 1811 and ending in 1820. Through this timeframe the king at the time, George III, was considered to have lost his mental capacity and his eldest son, also George, was made the Prince Regent (or Prinny) to provide for a competent head of state. In 1820, with the death of George III, Prinny simply become George IV and the political Regency ends. In contrast, as a stylistically term, the Regency covers a far broader timeframe - with no precise beginning or end point. Nevertheless, within the different disciplines of modern history, academics generally tend to think of it as starting in the late 18th Century and continuing through to the middle of the 19th Century. Here in Brighton, as we think about architectural heritage, this is perhaps an especially useful way of defining the term. I say this because Regency style appears in Brighton early, and is built into the town late, with sites such as Montpelier Villas and Park Crescent being designed and constructed around 1847-49.

As I touched on in the introduction, we are going to use the images in this picture pack to explore the transformation of Brighton from a coastal fishing town to a fashionable and fashionable resort site. The origins of this process lay further back in time that the stylistic Regency, as it is through the early part of the 18th Century, the 1720s, 30s and 40s, that Brighton first starts to undergo development as a spa resort.

Image 01 - This shows us Lambert’s view of Brighthelmstone, originally published 1765. This is several decades after spa development is first underway but structurally Brighton has not yet changes significantly. In this picture we see a town with a population of some 2,000 people, a market garden area to the north of the conurbation, and evidence of the adjacent downland being under cultivation for corn, straw, hay, etc.

Image 02 - If we move forwards some 14 years to 1779, this map (by Thomas Yeakell and William Gardner) evidences how the town is essentially set within West Street, North Street and East Street. Behind the town, you can see some of the market garden area noted earlier.

Image 03 - The next map (Marchant’s) moves us along nearly 30 years to 1808. Notice how by this point the town has expanded significantly beyond West Street, North Street and East Street, especially with development that’s occurred to the north of Brighton, over the area previously used for market gardening, and to the east of the Steine. Remember this area to the far side of the Steine, we will return to it in a few minutes time. Over to the west, there’s just a thin ribbon of development along the costal strip, this terminating against the Parish boundary with Hove. Hove village sits about a mile to the west of the Parish line and, in comparison with Brighton in 1808, is a tiny village, with a total of some 200 residents.

Image 04 - We can see Hove village in this 19th Century watercolour, painted from somewhere near to the Parish line with Brighton. Hove is this thin ribbon of development in the distance. Note how the village is separated from Brighton by agricultural land and that over here, to the left of the watercolour, you can see some of Brunswick Town under construction. Once built, Brunswick Town was initially isolated from both Brighton and Hove by these open field systems.

Image 05 - In this map (after Bruce), published in 1827, some 20 years after the 1808 work, you can see how in a relatively short period of time, Brighton has flourished, with lots of construction now visible to the west, north and east of the 'old town'. It’s in maps of the mid 1820s that for the very first time we see Brighton’s two great ‘new town’ developments, Kemp Town to the east and Brunswick Town to the west.

Another way to understand Brighton’s development through the period we’ve just studied is to consider population statistics. I mentioned earlier that mid-18th Century Brighton had some 2,000 residents. By the time the 1808 map was produced the population was passing 10,000 and when the 1827 map was published it was approaching 30,000.

Let’s now take a look at changing Brighton through one final device, the topographical view. The first image, (by Havell after Joseph Cordwell) we see Brighton in 1819, drawn from a site at the back of what today we call The Level. The second image (by Bruce) shows Brighton just two decades later, in 1839. The contrast in these images really brings home very powerfully how fast Brighton was growing through this period. Indeed, by some measures, early 19th Century Brighton was the fastest growing town in Great Britain.

Why was the town developing so quickly? Traditionally, Brightonians have offered two simple explanations. The first of the two explanations attaches to Dr Richard Russell, a British-born, European-educated physician who worked locally for most of his professional life. In 1750, Russell published his book: 'Dissertation on the Use of Sea Water in the Affections of the Glands'. Although written in Latin, as were all good medical treatise at tha time, it became hugely popular and unscrupulous people were soon producing illicit copies in English. In 1753 Russell retaliated, publishing his own formal English translation.

When we think of the salt water cure, as promulgated by Russell, and others in the medical fraternity of the time, we imagine women, wearing modesty gowns, being aided into the sea by ‘dippers’ as they exit the town’s bathing machines. But, in truth, there was far more to 'the cure' than simply bathing in salt water. The process was made mystical and complex in order that self diagnosis and treatment was not possible. Instead, you were reliant upon the expertise of your consultant, to whom you would pay a handsome fee in exchange for their knowledge. Your doctor would set out exactly when and for how long you might be in the sea and explain the necessity of consuming salt water, mixed up with products such as milk, tar, crushed crabs eyes, burned coral and many other compounds besides. In some instances, you might even have received advice as to where you should live relative to the foreshore and for how long you should daily expose yourself to the marine vapours.

The second traditional explanation for the success of the town is attached firmly to the Prince of Wales, subsequently the Prince Regent and ultimately, George IV. George first visited Brighton in 1783, aged 21. With his majority in place, his parents could finally no longer tell him what to do! George liked what he found in Brighton and returned regularly until the very last few years of his life; shaping and overseeing the construction of the magnificent Royal Pavilion in the process. In relation to George and Brighton’s development, the explanation is simple enough, it’s argued that his presence in the town attracted fashionable society and gave Brighton a social, economic and aesthetic edge over other evolving seaside spas.

It should be noted that both of these traditional explanations have substance, but that in reality there is a far more complex series of factors that underpin the town’s successful transformation into Europes premiere seaside resort. Amongst these are: Improvements to transport through the send half of the 18th and first half of the 19th Centuries, shortening journey times to Brighton and lowering cost.

The special status that the seaside comes to hold for late-Georgian and early-Victorian visitors. Here by the coast, many of the rules governing standard social interaction were relaxed, allowing people to more easily make new connections, explore opportunities for the marriage of their children, and seek improved financial investments… And, the speculative opportunity that Brighton came to to offer as it expanded - this evidenced in both the massive rise in service provision across the town, and in the improvements made to the town’s race course, gambling establishments, circulating libraries, assembly halls and housing stock.

The 1808 map depicted little streets to the east of the Steine. These small houses lining the streets provided Brighton’s first purpose built visitor accommodations and were constructed in the late 18th Century, to ensure that visitor provision was sufficient for us to avoid loosing out to rival resorts. An indication of the degree to which development took hold in the early 19th Century is that within less than 30 years, we had moved from building relatively unambitious small homes in little streets to whole new-town projects on the scale of Kemp Town and Brunswick Town.

As we touch upon the issue of urban development, we cannot but help turn our attention to Charles Augustin Busby. Born in 1786 to Dr Thomas Busby and his wife, Miss Angier, C A Busby was the principle architect that shaped the development of late Regency Brighton. More of today’s listed architecture is designed by him than any other, including the two great estates of Kemp Town and Brunswick Town. Residents of London, Dr Thomas and his wife were social and political radicals of the age, with close attachments to some of the most talented figures of the period. Within their social circle were Willian Blake, Byron and Merlin the Ingenious Mechanic. While working as a professional musician, a translator of Latin and Greek, and a Georgian newspaper correspondent, Dr Busby and his wife home educated their children through to their teenage years. At which point, what they considered their natural aptitudes were identified and the children articled them into relevant professions.

For Charles Busby the selected route was architecture and pupilage in the drawings office of Danial Asher Alexander, one of the Regency's great designers. Busby was also fortunate in that he gained admittance to the Royal Academy's school, then a fairly new establishment. In 1807, as he attained the age of 21, Busby graduated the Royal Academy with their Gold Medal, evidencing his status as an outstanding talent, and left Alexander's drawings office to embark on an independent career. This went well and, as it progressed through its early phase, the French wars came to an end, opening the opportunity for the young architect to undertake a Grand Tour of Europe. But Busby had inherited his parent's radical social and political views, and the ‘Old World’ was of little interest. Instead it was to the 'New World' that Busby aspired. Soon he was on a boat across the Atlantic, landing in Manhattan. He lived for a period in Wall Street and Nassau Street during which period he joined the great scientific institutions of the city and contributed drawings to Blunt’s, Guide to the City of New York, published in 1817. Soon busby was traveling through the eastern seaboard states meeting the great and the good, recording novel American construction projects, and contributing his own architectural designs at the behest of clients.

During 1819, Busby returned to the UK. Shortly after this, it is thought that Busby visited Brighton for the first time, most likely at the behest of Thomas Reed Kemp, then one of the richest men in Sussex. Kemp was seeking to develop a large new town project to be named after him, and it’s thought that he wanted a top flight architect to co-design the scheme, in tandem with a local builder/architect already known to him, Amon Henry Wilds. The two men’s work for Kemp was completed fairly quickly, as once the designs were produced Kemp made it clear that he would oversee the building of the new estate and that he had no further need of the pair. Wilds and Busby sought employment elsewhere around the town and found many commissions, albeit they dissolved their short-term business partnership amid some acrimony. Within a year of the Kemp Town project starting, Busby had agreed with another local landowner, the Reverand. Thomas Scutt, that he would participate in a second large scale building enterprise. Scutt’s land lay to the west side of Brighton, on the south-easternmost part of the Parish of Hove. The ‘Memorandum of Agreement’ to build Brunswick Town was signed by the two men on 11th November 1824 and large scale works were very quickly underway.

In this early plan, in his own hand, we can see Busby’s design for Brunswick. It clearly illustrates how Brunswick Square forms the centrepiece to the estate, with large houses being laid down for affluent residents, and these continuing along the coastal strip to the east and west in the form of the Brunswick Terraces. Around these grand terraces there are mid-sized properties forming streets for the middle classes, for example in Waterloo Street and Lansdowne Road. While, wrapped around these locations are smaller properties still, these offering accommodation and opportunity to the working classes. For the different socio-economic groups coming into Brunswick Town, Busby offered what he considered the appropriate infrastructure. Over here we see him setting out a chapel and, to the south of that, a public bath. Opposite this, we see him introducing the Kerrison Arms Inn, a family hotel for the more affluent visitor while, to the north and west of this, there is to be a covered market and shopping district. To the west of Brunswick Square itself, on this strip of land, Busby introduces both police and fire stations and adjacent to these an office for the Brunswick Commissioners, men who under the powers granted to them in the Brunswick Town Act, will govern the estate. It’s worth reinforcing that within the Parliamentary Act for Brunswick we see the evidence of the development being a town in its own right.

Busby had great talent but little money. Scutt had both land and funds, but he was reluctant to risk his fortune on developing Brunswick Town alone. Instead, the two men set about employing the ‘urban speculative development model’ to progress construction. In this, investors were recruited to risk their funds and build to Busby’s designs and building regulations, in the hope that a well designed outcome that would be to the economic advantage of all concerned. Busby’s initial concern therefore quickly became the recruitment of investors. To attract them he produced what are often called ‘client drawings, these showing the fine properties that it was proposed to build, including both the front elevation of the house and its plan form.

On this plan we can see, along the bottom of the page that there’s manuscript. On the original sheet, this reads: Plan of Mr Charles Elliot’s house Brunswick Square, agreed for £3,000 to be finished complete. Under this line of text you can see that the document has been countersigned, on July 5th 1827, by George William Sawyer. He is the builder employed by Elliot to undertake the construction. The two men are effectively contractualising the document with the agreed price for the job. Furthermore, across the sheet, on top of Busby’s annotations, they are writing in the details of the room finishes to be supplied for the construction fee. Here, in the front basement room, for example, you see a brick floor specified. While here, in the ground floor front room, the dining room, you see that the finish is noted as being in ‘stucco and paint’. On the 1st floor, the main rooms are to be decorated with paper at 1shilling per piece. While, higher in the house, the quality and cost of wallpaper is reduced.

Busby then goes further in exercising control over the build process, producing detailed drawing for those undertaking the construction process, as can be seen in this image. The written text around the sheet sets out how to proceed with the making of foundations, details of the mortars and renders to be employed, the dimensions of the main timbers in the property, and much more besides. If we zoom into this image we can see Busby’s attention to detail. Here, you can see he notes the size of windows, here, the directions and dimensions of floor joists and, here, how to reinforce cellars where this is thought necessary.

We are now almost ready to start exploring the rooms in No. 13 but, before this, let us end this section of the tour by taking a look at the interior of a large Brunswick property during the Regency period. We can do this by looking at a series of sketches produced in 1840 that illustrate the interior of No. 32 Brunswick Terrace.

Image 18 - ground floor front room, the dining room. In this drawing we can see the corner of the main dining table and a half of the side board. Note that in this south facing room, we have a partially open sash, through which we can see some of Brighton’s fishing fleet at work on the sea. The windows are finished internally with poles and drapes, wooden venetian blinds (which were very popular at the time), and so called sun or ‘snob’ screens. These clip to the lower sashes and articulate with them as they are moved. The screens were often manufactured in green silk and they have an obvious use in a home with a pavement directly outside of the ground floor windows. Notice the lamp on the sideboard. Gas was plumbed into Brunswick Town for street lighting from inception, but there’s a lot of evidence that many homeowners were initially reluctant to use gas internally, being fearful of explosions. There’s no evidence of anything but candle and oil lighting in No. 32 in 1840 when these sketches were produced.

Image 19 - This drawing takes us up to the first floor of the property, where the drawing rooms are located. Here, you can see a markedly improved standard of finish: with fully fitted carpet (Brussels weave) up to the skirting boards, a ‘drugget’ covering the expensive carpet to protect it from day-to-day wear and tear, pelmeted curtains - which by the late Regency had become very fashionable, instruments for entertainment - the hard and forte-piano, and, a flower stand - signifying the increasing importance of plants to the interior of the domestic property at this time. Finally, note how all of the furniture is disposed across the room, much as we would have it today - in earlier times, it would have been set around the four walls most of the time. Much of the way we live in our houses today hails from this period in history.

Image 20 - Our final picture takes us up to the second floor of the house, where the principal bedrooms and dressing room to the property were located. In this sketch we can see how the main bedroom was finished, with a large fashionable bed, a wash stand and commode adjacent, and a dressing table with chair and mirror. Notice again, how an expensive carpet is laid across the floor.

This section of the House Tour is specific to the Dining Room. The Ground Floor front room So, we’ve walked into the Ground Floor front room of the house. Some of you may remember from the plan-form of Charles Elliot’s house we were looking at earlier, that this is the dining room of the property. When people enter this room, many comment first of the extraordinary colours seen on the walls. We are currently in the process of returning the room to its original finish.

This raises the question: how do you explore the colour history of your home? That’s what we are going to cover now. There are two completely different ways to explore the colour history in a property. The first is quick and inexpensive but it does not provide a definitive outcome. Let me describe this procedure for you. You start by identifying a fairly large area and using sandpaper of a scrapper tool to abrade the surface away. Here we’ve clearly created a large circular ‘rub’. As you work, you reduce the grade of the paper you’re using until, eventually, you’re using polishing cloth, as you might on the body of a car. The aim of course is to open up a view, in ring form, of the different paint layers applied over time. If you undertake this type of investigation there are are several things to remember: A) You must rub through all of the paint layers, back to the surface that’s first decorated. The small white dots in the centre of this rub evidence the plastered wall. If you don’t do this, you don’t know where in time you are! B) One is never an experiment. The central colour in this rub may be the original paint used across all of the walls but equally, the area we’ve exposed could just be showing us one petal that’s a part of a giant floral pattern. We need lots of rubs to understand what is beneath the later layers. C) If we’re rubbing our way through the paint layers in the upstairs rooms of a fashionable 18th or 19th Century house, it’s almost certain that the paint we’re removing is lead based, and lead is a neurotoxin that we need to handle with care. It’s dangerous to all of us but especially so to developing embryos and infants. So, you need to be especially careful to screen them from the tiny particles that are generated during the abrasion phase. With a little bit of suction and care as you work, this is not overly difficult, but don’t take off your overalls in the kitchen at the end of a days work and then feed the kids tea from the kitchen table!

Somewhat counter-intuitively, when you first expose old lead painted decoration, you don’t see the original colours used. You have to wait for a few weeks while ultra violet light bombards the surface and helps revert the colours to what was original seen. Further, some colours, especially light ones, don’t fully return to their original finish, because another component in the paint was linseed oil and over historical time this darkens and cannot be lighted upon exposure to light. So, light colours always look to us a little darker than they were fist seen.

The second approach to investigating colour history provides for a way to correct for this problem, and some of the other downsides to the simple investigative method I’ve just explained. This involves turning to micrography. Essentially, we take a scalpel, or a similar tool, and cut away from the wall a small sample of the paint layers and the substrate to which the paint is attached. Generally, a fingernail-clipping-sized-sample is sufficient. This is then placed into resin and, once set, the resin block is cut in half, and the cut face is polished. The prepared sample is then placed under a microscope and the view enlarged several hundred times. At this type of magnification it is possible to see the individual layers of paint and even the pigments in each layer that are providing the colours. With this information to hand, it’s possible to recreate the chemistry of the paint should it be felt necessary and the colours obtained without oil discolouration can be viewed. Aside from this benefit, the micrographic view ensures that we fully understand each layer that’s been applied to the wall, something that’s impossible with the rub technique. There’s one further benefit this second method of analysis offers. We can compare the layers of paint on different parts of the room to see whether they accord with each other or are grossly different.

For example, let’s pretend that there are 26 layers of paint on this south wall to the room, with the first four colours being, purple, blue, green and red. if I looked at a micrograph from the north wall, I would expect to find the same number of layers in the same colour sequence. If I did not find this, say for example there were only 22 layers of paint and the first four colours, purple, blue, green and red, were missing, I could hypothesise that the wall was either stripped of these four finishes, something that would be visible in the micrograph as a noise interface, or that the wall was built later than the wall to the south. I think you can probable see that if you were undertaking a historic building analysis, information like this can be of incredible value; allowing the investigator to separate what amounts to the significant from the insignificant. For example, an original Robert Adam decorated wall from a 20th Century partition decorated in similar colours but not actually an 18th Century feature.

So, we’ve discussed the investigative process, now we get to the matter of why do we find particular colours in historic houses at any given time. Today, if we want to decorate, we generally collect a paint chart from a merchant’s shop and select the colours that we like, we have thousands of colours to choose from. But, until the mid 19th Century, decorators had a much reduced colour palette from which to select - less that 200 pigments. Furthermore, over past centuries there have often been theories in place to influence people’s colour choices. Colour theory goes back to a pre-Newtonian period and has had many exponents. By the early to mid 19th Century one of the most hight regarded of these was, Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe, 1749 – 1832 (Pronounced, Yo-han Volf-gang (Fohn) Guh-teh). Goethe’s theory held that the colours we have here in the dining room, so called Peach Blossom colours, had a special quality, because they influenced humans in ways that aided digestion and the appreciation of food. With this in place, it became fashionable, for a short time, to paint dining rooms in such colours. We think this is why we see them being used here.

Let’s now move on the overall finish of the room. The painted plaster walls and timber fittings would have been complimented by silk curtains in a room of this calibre, these almost certainly in red, this was the preferred colour for dining rooms in the early 19th Century. On the walls, it was common to find paintings and in dining rooms these were usually either still lifes, of fruits or vegetables, or hunting scenes, perhaps, showing hounds chasing deer across the downland. Across the floor would have been a rug, you can see the stained boards to the edge of the room evidencing this. Fitted carpet was available in late-Regency homes but was generally not used in areas where people ate - as rugs were easier to lift and clean. On top of the rug would have been a table seating 18-20 people for a meal, this perhaps in Cuban mahogany or rosewood and beautifully finished with fine linen, upscale china, cutlery and glass, and silverware, including candelabra. The long walls of the room would have been fitted with side tables, for staff to maintain service to guests, while at the far end, between the columns and under the frieze, would have stood one of the centrepieces of Regency family life, the sideboard. On this, there might be more fine silver, a mechanical instrument, or perhaps sculptures., while above, the family might have hung another picture. Beneath the sideboard would have been a cellarete, a metal lined wooded box filled with ice, chilling some of the wines and champagnes to be consumed with the meal. The columns themselves have not yet been redecorated into original colours, when finished they will have black bases, stone coloured fluted timber pilasters and ivory white capitals. The overall effect of the room, with the expensive finishes I’ve described and the complementary rich plaster ornament we see above us, was specifically designed to impress guests - to set them at ease about the status of the family they were joining and to encourage them to enter into appropriate dialogue, about such issues as the marriage of children and improving financial investments!

We’re stoping here in the hallway to talk briefly about the decorative finishes used in this part of the house and, thereafter, to discuss building materials.

During our investigations in this area we discovered that out entrance lobby, which you can look at in detail as we exit the building, was originally decorated with paint in imitation of rectangular stone blocks - a schema that’s called ‘blocking’. What’s been exposed in the lobby is, we think, the poor quality work of an apprentice, this later being overworked by his master. The idea behind blocked decoration, which was very popular in the Regency, was to suggest that a gentleman’s house had been made using stone, the appropriate building product for an affluent owner! Of course, the occupants and their guests knew the property was not actually constructed of this material, but it was something of a fashionable necessity - perhaps the marble finished Formica table top of the 1960s! Here, in the hallway, our sampling has revealed the early use of green and pink colour-ways - you see some here as we return to such a finish. In fact, the first three schemas here were all in green and pink. We have surveyed many local period properties and found these same colours in numerous hallways, evidencing the popularity of this finish during the Regency. Interestingly, after the green and pink phase, the walls of our hallway were also blocked, initially in the dark brown finish seem in the lobby and later in a lighter stone colour. By the late 19th Century, the blocking here was being replaced with Lincrusta, a deeply-embossed wall covering invented by Frederick Walton in the 1870s. This was applied at low level, a dado rail was introduced over the Lincrusta, and gold foiled wallpaper was applied above the rail, all the way up to the cornice!

The second reason to stop here is to discuss, building materials, the products from which the house is made. From the street, people see homes with rendered facades, the render, yet again, being used in imitation of stone. This device was a necessity locally, as there is no significant stone deposit in our area, and importing the volumes need to raise whole buildings in stone would have been prohibitively expensive. Behind the render to the main facade is brick; this material came to be widely used in historic Brighton, as clay is a local resource . In fact, the clay, or ‘brick-earth’, used in the construction of Brunswick Town is so local the the source lies just outside of our front door; the area of the garden in today’s Brunswick Square being excavated to form and fire bricks. We have our local clay because of the last Ice Age. 10,000 years ago the beach lay some 200metres north of where we see it today but, as the ice receded, the melt water transported clay southwards and pushed the beach line to its current position. So, underneath us, is an 8-10metre deep seam of clay sitting on the old chalk seafloor. It is this that was exploited to produce the bricks required for the building of Brunswick Town.

From the time our Georgian forefathers started construction here, there had, for many centuries, been a locally available alternative masonry source, this being known as bungaroush or bungaroosh - a product that we might simply describe as flint and lime walling. Given the availability of this, and the then relatively high cost of bricks, bungaroush was widely used by those in the construction industry. Brick production was expensive because of both the human effort involved and the expensive fuel required for firing. There’s no definitive origin for the term bungaroush. Some say its root is associated with throwing rubbish out, others that it’ derived from old French for small sweets! From whatever source it came into use, it’s worth noting that while flint and lime construction appears in many parts of Britain (where such geological resources are found locally), only in this immediate area is the material known as bungaroush. If you visit many parts of Georgian Brighton, bungaroush is hugely in the ascendancy, with perhaps 80-90% of the masonry component of a property being formed from it. However, here in Brunswick Town, the architect Charles Busby insisted that the front elevations of his homes should be in brick. This, and that fact that the main rear elevations are also sometimes in brick, means that the ratio of bungaroush to brick in this estate is closer to 3:2.

Despite being our most dominant local masonry product, bungaroush is a relatively poorly understood product, so let’s consider the material in a little more detail. The lime that binds the mortar in which the flints are set in a bungaroush mix is derived from burning the chalk that forms our downland. While, the flints themselves are found as cobbles on the beach (rounded by the action of water) and as large irregular-shaped nodules on the farmland around and about. But let’s go a little deeper! Our chalk was formed some 60m plus years ago and results from the calcium rich exoskeletons of tiny marine organisms, that, as they died, precipitated to the bottom of the ocean and aggregated. Our flints were once sea sponges, lying on the bottom of the same oceans. Living sponges are rich in silica spicules and, over geological time, it was this material that was transformed into the glassy rocks we have today. So, as Brighton started to develop as a resort town and homes for visitors began to evolve, our seaside properties were being constructed from the remnants of the animals found in the sea, it’s all rather poetic, isn’t it? While were on the topic of masonry construction lets think about one last issue. I’ve mentioned that lime formed the binder holding together the mortar component of the bungaroush. The same type of lime also bound the brick mortars and the internal plasters used in the making of these properties. These lime-based products have a very special characteristic. Unlike modern plasters and cements, lime-bound mortars are fully recyclable, which means that if a masonry component within a traditionally built property suffers failure, we can isolate the mortar, knock it back to its constituent granules, add more lime binder (as originally used) and re-purpose the mortar to repair the building. This strategy provides for the best repair mix available (one that is identical to that originally used), it keeps our financial outlay to a minimum (because we are purchasing only a small volume of lime binder), and it’s planet friendly (because we are not replacing the original masonry with ‘carbon mile rich’ modern fabric.

Let’s recap. The front of the building is in brick, the party walls between the houses and the rear elevation to the property are in a mix of brick and bungaroush. These masonry structures provide for a box, inside which are the rooms of the property. At basement level, the internal room partitions themselves are also in masonry but, perhaps surprisingly, none of the rooms to the upper floors of the house have internal masonry walls. Instead, these apparently substantial looking walls are formed in softwood stud work, over which there is just lath and plaster, the surface receiving the paintwork.

Of course the timber work in the house is more extensive than this. You are stood on a wooden floor pan here at ground floor level, and there are more of these at first floor, second floor and third floor levels. While, above these are the rafters and close-boards to which the roofing slates are nailed, in order to repel rainwater. Unlike the masonry, all of which has been sourced locally, none of the main softwood members to the house are British, because by the Regency, we have no economically priced construction timber left, having earlier cut down our trees for the building of boats. Almost all of the timber from which Brunswick Town is built hass being imported from the Baltic, the cold northern states of wester Europe where trees grow slowly and develop huge strength as a result. The engineering capacity of the softwoods used in these houses if closer to that of oak that it is to the modern, farmed, softwoods of today.

The timbers Busby specified to build these houses, were sailed across the North Sea and along the English Channel to the port of Shoreham, some 5 miles to our west, where, after the appropriate taxes had been paid, it was loaded onto ox-carts and drawn along the turnpike (todays seafront road) into the building sites of Brighton and Hove. So, we are a property that in part is made of local materials and is otherwise formed of fabric sourced from far away.

The cast iron fireplaces, kitchen ranges and staircase balustrades used here are further examples of mostly locally produced products, Brighton and Lewes sustained numerous successful manufacturers.

The mahogany handrail was from the tropics and the paving slabs outside in the streets were from the South West of Britain are further examples of product carried over great distance.

Lead the group up the stairs, enter the rear Drawing Room and stand just inside, while you direct the group into the front Drawing Room. This section of the House Tour is specific to the first floor drawing rooms.

Welcome to the first floor of the house. This level of the property was generally developed to provide for a front and back Drawing Room - albeit occasionally the rear room could be purposed to serve as a bedroom.

The front and back drawing rooms each have their own door. This is so they can operate as two seperate rooms when the folding doors between them are closed.

There would be folding doors between the front and back drawing rooms. The doors, in four leaves, were mounted on ‘Parliamentary hinges’ that enabled them to be part-opened, or folded all the way back to join the two rooms into a single suite. The folding doors, in four leaves, were mounted on Parliamentary hinges so that they could be part opened or fully folded back to co-join the two rooms into a single suite. During the daytime, the doors were often left closed. In the morning, the rear room perhaps being used by the ladies of the house for reading, writing, sketching and the like. While in the afternoon, children may have rehearsed with musical instruments in the front room.

By the time children were being sent to bed, and the family were in full entertainment mode, the doors between the front and rear drawing rooms would be thrown open, so that after a meal in the Dining Room, guests could gather in groups across the increased floor space, and settle in for a few hours of convivial conversation.

Georgian families paid a premium to obtain a house to the ‘preferred east side of a square’, because the orientation of the property to the position of the sun throughout the day meant they would outlay less money on artificial lighting over the course of a season.

Because the drawing rooms were co-joined in the evenings, the two parts were very often decorated as a single suite, with matched ceiling centres, cornices, fireplaces, skirting boards, curtains, carpets and wall decorations. This is how we believe these two rooms were treated and, by looking at the original fabric still visible in the front room, you gain an idea of the original finish. What you’re looking on the front room walls is the second layer of oil paint ever applied. The underlayer being plain and, we think, not used for very long. As you can see, we have a geometric scheme here, with brown panelling applied to a green background. If you look closely at the interface between the two colours you can see puncture marks in the plaster and, if you zoom, at a very high level of magnification, into the groves left in the paint by the brush, you can find tiny fragments off gold. This suggests that around each brown panel there was originally a moulded timber surround that was gilded.

If we look to the inside of each panel, you can see further archaeological evidence of the original finish to the room. Notice on the north east panel you can see evidence of where picture frames once hung. The same is true in the panel opposite, and in both similar panels to the west side of the room. In fact, if you look to the top of this south west panel, you can actually see evidence of the cord that was suspending a frame in this location, the ‘shadow’ of the cord forming an apex that drops to either side of the frame.

The centre panel on the north wall has an altogether larger frame. You can see the mounting points for this along the base, the left and right edges and the top of the frame, with corners clipped at 45 degrees. This frame held a mirror, the purpose of which was to work with a slightly smaller mirror positioned above the fireplace. The two mirrors in the front room were strategically placed to work with the windows inset to the bow front of the property. Notice how the windows drop to the floor, allowing the occupants of the house to view an ‘idealised nature’ through the glass panes of the sash windows. If you stood here, slightly to the east of the large mirror, you would also have an optimal view of the sea - the windows and mirrors combining to bring the land and the water to the inside of the home.

Having paid £3,000 to develop a property Brunswick, ‘finished complete’, you’d acquired glass in the windows and fireplaces in the rooms, but the house was otherwise bare.

Your next step was to furnish the home to the required standard. For this, you needed rugs and carpets, furniture to sit on top of these, paintings for the walls, baubles and instruments for the fireplace mantle shelves, (Chinese porcelains, European soft pasteos, and clocks, for example) and, of course, mirrors and chandeliers. Some of these objects could be hugely expensive, perhaps each costing as much as 10-15% of the build cost of the property. Above the drawing rooms were the bedrooms and dressing rooms of the house, generally finished to a lower standard that the public reception areas where guest were entertained but, nevertheless, all demanding further outlay. Additionally, of course, you needed your transport solution (horses and carriage) and your staff, all of whom needed livery and, like the anilines, regular sustenance.

It was a very expensive game sustaining a seafront property in Regency Brighton and, any suggestion that you might be financially challenged in doing so, would quickly result in you being ‘cut’ from society. The information we’ve discussed here about the 1st F brings to mind an obvious question, who were the original occupants of these homes? Who were the people rich enough to meet the costs of being here through the height of the season? If we turn to the directories and other records of the period we can discover the early residents; people like the Duke of Bedford, possibly still the richest Englishman in Great Britain, the Duchess of Dorset, Earl Whitworth, and Princess Lieven, the wife of the Russian Ambassador. Interestingly, even for this type of person; sporting unimaginable wealth (much as a modern Russian oligarch does today), there was a point at which excess expenditure was reigned in and, here in the front Drawing Room, we have an example of this. The room appears to be detailed in satinwood. We can see this in the architraves fitted to the windows and doors and in the skirtings. But not even the richest in society actually thought it made a great deal of sense to fell satinwood trees in Asia or Africa and import them to Europe for the purpose detailing interiors. Rather, the expensive joinery seen here is something of an illusion, like the blocked wall decoration we were speaking of earlier. Our satinwood finishes are nothing but paint and stain once again, applied over moulded softwoods. If we visit the Royal Pavilion and admire the acres of satinwood detailing there, the same situation prevails, yet again it’s all a decorator applied illusion. Besides the financial saving, there was a further advantage to this approach, it allowed the occupants of the house to respond quickly to changing taste. If rosewood or walnut became the new de-rigour finish, a specialist painter could be called in and, by the time you staged your next soirée, a completely refreshed interior could be presented to guests! We’ve just spend some time talking about the richly finished guest reception areas of the house, and I’ve alluded to the private bedroom areas above. It’s important to view a historic house as having a hierarchy of rooms, which from the G and 1st Floor levels generally diminishes with each floor. Well, enough of the affluent owners of these properties and their foibles, the final part of our journey takes us below stairs to consider the life of the servants, are there any Qs before we move to our basement in No. 10 Brunswick Square. Once any Qs are dealt with say, ‘Please follow me down to the Basement’.

Note G: Lead the group down the stairs, make sure everyone is with you and then open the front door and proceed from No. 13 down to No. 10. At the top of the basement stairs outside of No. 10 use the safety warning that starts PART 3.

PART 3 - The LGF in No. 10 Note H: This section of the House Tour is specific to the LGF at No. 10. Note I: With everyone standing at the top of the basement stairs to No. 10 say: ‘A brief safety warning, the servants steps to the basement are steep and it’s easy to trip, please use the handrail and descent carefully, we haven’t had an accident yet and we’d like to keep it that way’ :-) LGF No. 10 Front area:

We are now stood in the front area to the property. Here, you can see that there’s a number of doorways inset to the elevations, most of these accessing brick vaults for the storage of coal. There are 20 or so fireplaces in a property of this size and all were kept alight through the cold months of the year for the comfort of the family and their guests. Additionally, we have a small cellar under the stairs. Often on Busby’s house plans this space is annotated as being for the storage of dust. Dust is sloughed off human skin, which collects around us in our homes. This, and the ash from the open fires, was swept up by the servants and stored for recycling into the agrarian economy, as fertiliser. Finally, there’s an additional cellar, [here, the N-most cellar], for the storage of small beer - low alcohol beer. Every large house of this size in Brighton was so equipped, as there was a general distrust of drinking fresh water in the period and fermentation was thought to make water safe for consumption. Inside the property the layout of the basement is fairly typical of that found in large Brighton town house of the period, and is as follows: The front room provides for a Housekeeper’s Room Behind this is a Wine Cellar, Servants’ Hall and Butler’s Pantry, and beyond these are, semi detached from the main block of the house are the Kitchen, Scullery and various Larders. Let’s go inside and explore in more detail.

Note G: Lead the group into the hallway, stopping just outside of the Housekeeper’s Room.

As I mentioned a minute ago, the first room in the basement sequence is the Housekeeper’s Room. Please walk in, [indicate the way with your left arm] and I will follow. The Housekeeper’s Room The Housekeeper was the senior female servant in the property, with overall responsibility for the general routines and regiments of the household. From here, she issued orders to her junior staff to maintain the building, she maintained the accounts for which she was responsible and, in the lockable cupboards around the room, for example [here] besides the fireplace, under the windows and in this large walk-in store, she kept the goods for which she was directly responsible, when they were not actually being used above stairs, things like expensive china and linen. Her role, in relation to these goods, was to act as an auditor. There was a lot of pilfering out of properties like this, and one of the Housekeeper’s roles was to minimise loss. The explanation behind the losses is fairly easy to understand. Most Brighton servants were not themselves Brightonians. Rather, such staff were drawn from the outlying villages and town of Sussex, Surrey, Kent, and beyond. For generations their families had been agriculturists but, the Enclosure Acts of the period, were shutting down the ability of such people to survive on the land. Many youngsters were forced to leave home and seek employment in the rapidly evolving industrial and urban spaces. For those selecting a life in service, and ending up in a house such as this, there was a strong temptation to pilfer items such as napkins and cups, and sell them on the black market in central Brighton - sending the much needed funds raised in this way back to those left in the countryside.

We can see the extent to which this type of theft was common in the period by looking at the town’s criminal records and newspaper reports of court cases. We can also note, in these sources, that the penalties for such transgressions could be very severe. In here today, you see the result of our efforts to return the room to its original configuration. We have dug out some 16 tons of modern concrete flooring and reintroduced floor boards, We have also extensively repaired the plasterwork to the room, using the techniques I described earlier in the hallway at No. 13 - the crushing of defective plasterwork back to its component granules, the refreshing of this with new lime binder, and then the reuse of the mix to effect repairs. We have repainted the walls in the room to showcase the original colour, and we’ve re-introduced grained timber work, as was first used. This, as you can see, is imitating oak, albeit the effort made provided for one the lowest quality of oak grain, a simple drag finish. The starting point for all the timber work in a basement in this period was to paint it in so called ‘House Brown’, an inexpensive, earth toned, colour. However many families wanted to reinforce the downstairs servant hierarchy (senior to junior staff) and a way of doing this was to provide additional decorative effort in the rooms of the senior servants, So, while junior staff lived with drab finishes, senior staff sometimes saw the cheapest version of oak grain, ‘drag’, laid over the House Brown - a little something of the upstairs applied downstairs to bolster the status of the management! Reading these types of symbols for us today is difficult, they are not a part of our modern world but, for the people of the period, they were as obvious as is a winged statue of a lady on a car bonnet to us today. In closing my presentation about the Housekeeper’s Room, let me note that she would have anticipated and aspired to a bedroom at the top of the house, but if needs be, she would have slept down here at night.

The Wine Cellar

To the far side of this east wall to the Housekeepers room lays our Wine Cellar, which is in two parts Adjacent to this green painted section of wall is the inner sanctum to the cellar, with a capacity of over 3,000 bottles. Adjacent to the piece of cream painted wall in the entranceway to the Hk’s room, is the day cellar, holding the wines required for use in the immediate future. The cellar is positioned deep within the property, far from the external walls of the house, to improve security and reduce the risk of break-in. Further, it does not have a lath and plaster ceiling, as is seen here in the Hk’s room. Instead, it utilises brick vaulting, which is far more resistant to being penetrated. The fortification of the cellar is taken further. There is a door to the day cellar in the hall corridor, and beyond this a second door securing the main cellar, this being lined with sheets of iron. Each doorway boasts giant timber sections, huge locks and keeps, and very strong hinges. Fully stocked, with the best of the Premier Grand Cru then available, the value of the cellar contents might start to approach the build cost of the house, it is this consideration that explains the security measures we’ve discussed and which motivated owners to keep pistols in their homes with which to repel intruders, should it become necessary! As we walk through the hallway in a minute, on our way to view the Servant’s Hall, take a second and look into the wine cellar and take in both its size and security measures.

Note J: Lead the group back into the hallway, stoping them just outside of the Wine Cellar (in sub groups if required) and place yourself in the doorway, there, use a torch/phone to illuminate the features discussed. Thereafter, ask the visitors to turn right and follow the route through to the Servants’ Hall - reminding them to be wary, should any objects have been left on the floor of the Hall which might represent a trip hazard. The Servants’ Hall

There were generally 8 to 12 servants working in a house of this size and in this room, the Servants’ Hall, they would have eaten their daily meals and stored some of their possessions, hence the two closets either side of the small fireplace. If bedroom spaces at the top of the house were fully taken, this room is also where female servants may have had to sleep . The convention about sleeping downstairs, were it to be necessary, was that male staff got the Kitchen floor and female staff the back of the Servants’ Hall. You can see here, in this alcove, the space I’m talking about. it’s not very big but, at a push, it could sleep many women, who could find themselves using box or bunk beds. Notice how the floor in the alcove is again of suspended timber, as in the Housekeeper’s Room. This may seem like a small point to us but it is a good illustration of the care that could be put into room design in the period. Servants waking here must have been grateful that their feet initially went onto warm floorboards rather than the cold flagstones of the Hall itself. Servants worked six and a half days a week, with half a day off on Sundays - for either going to church or visiting family and friends. The reality of servant life was that very few could make visits to family members, as they were far away in the countryside. Faced with this challenge, life for many in service became something of a secret, as it was felt that to disclose the reality of their circumstances might lead to dismissal. We can see this happening to William Taylor, a footman, who in 1837 maintained a diary for a year about his life.

William had met a young woman and married, placing her in a room close to the townhouse in which he was employed. She became pregnant and subsequently delivered a child, but even then, William found it impossible to contemplate telling his employer about his circumstances, fearing that dismissal might follow due to him having a set of interests in conflict with his employers wish to call upon him day or night. If 19th C social history appeals to you, look for William’s diary, it’s available from the Marylebone Society for a very modest fee, the title is simply: DIARY OF WILLIAM TAYLER, 1837. One other point about the work, William was a London-based servant but was brought to Brighton for three and a half months in 1837, so you get read about his experiences in both locations. Servants frequently started work aged 14-15, and at that point in Brighton they typically earned about 12 pounds 10 shillings per annum (£12.50p). If they made a career of service and obtained promotion, as senior servants they might earn £65-85 per annum, with tips. Brighton servants in the Regency were highly paid, even by London standards. The servant’s objective in life was to either gain a senior position and become largely a manager by middle age, or to have saved sufficient funds by this time to leave service and earn a living through commerce, perhaps buying a small store or hostelry to sustain them into old age. This transition was something of a necessity as the physical demands of service in a large house were increasingly difficult to meet as the years rolled on - think about having to daily move water, food, coal, furniture, etc., up and down a property with 6 or 7 flights of stairs! Are there any Qs before we journey back out to the hallway?

Note K: Lead the group back into the hallway, stoping them just outside of the entranceway to the rear yard.

Butler’s Pantry We have stopped here to briefly talk about a number of issues, let’s start by noting that we’ve just walked past the door to the Butler’s Pantry, into which we are not going today, as it’s full of furniture awaiting repair. The Butler of course, was the senior male servant in the house and in his Pantry he sat guard over the Silver Safe. Bell Board Outside of the Pantry, on the opposite wall to the door, you see the remnants of the bell board. When a bell pull was employed upstairs in the house, a cord caused its bell at this end to ring, the tome of an individual bell and the metal plates below the bells signifying to the servants where their attention was required. Rear Area To my left, [here], is the entranceway to the rear area (or rear yard) of the house. Outside in the yard, on the far wall are a series of lean-to structures set against the party wall with No. 9, these provide for: an ice larger a fish larder and both male and female privies (earth closets that require emptying on a regular basis by the so called, night soil men. We are talking now about a period before germ theory and it’s not seen as especially problematic that the doors to the privies are only some 8 feet away from the cap stone to the well for the house. This descends some 12.5 m into the ground and, even today, sits with some 2 m of water at the base. This reserve is chalk filtered water front the downland to our north.

When it rains, the water quickly penetrates the thin turfy layer of soil over the downs and then seeps slowly through the porous chalk matrix, as it makes the journey towards the sea. Here in Brunswick Town, we are simply connecting to the water supply before it reaches the beach. By the way, you can still see the downland water making this journey, just visit the beach at low tide to see fresh, chalk filtered, water cascading across the sand and pebbles. In contrast to the old fashioned toilets the servants were obliged to use, upstairs in these houses Busby had specified WCs, which he had the good sense to connect to a sewer system that discharged into the sea. Fashionable people loved this new invention, introduced over 30 years before Joseph Bazalgette sewered London, but they weren’t about to pay for such expensive technology for their employees!

Water was not generally consumed in its natural form in the Regency period. The well-water drawn here would have been boiled before being used for cooking, and otherwise been consumed for the purposes of bathing, cleaning, watering animals, etc. Beyond here, the corridor leads us to the position of the rear staircase to the house and the Larder, Kitchen and Scullery areas. Houses of this size generally have either one or two rear stairs - that the servants use to negotiate the property without being seen off the grand stairway that we were using in number 13. As you will see, we are currently in the process of reinstating a flight of stairs to illustrate this route. Unfortunately, we cannot actually use the staircase, as families now live in apartments above us.

As we move towards the kitchen, the first rooms in this area serve as a meat safe (or larder) and game larder. As you can see if you look into the meat safe, above your head are timber beams and attached to these are hand-made iron hooks. Carcasses were suspended from the hooks and the mesh walling around the safe allowed air to circulate and help maintain the provisions in good condition, while limiting despoliation by vermin and flys. Remember, there was no active refrigeration in this period, so strategies such salting, drying, meat and pickling were common ways to preserve goods. the sort of thing that might have hang in here would have included the great side of ham we sometimes now see in upscale delicatessants.

Kitchen & Scullery. This is by far the brightest room in the basement, bright in large part due to the presence of the large skylight to the centre of the room. The function of the skylight is twofold. Of course, it’s intended to let light into the kitchen, this to minimise the quantity of artificial illumination the servants require, no one wanted staff burning more candles and oil lamps that was absolutely necessary. The second, perhaps less obvious function of the skylight, was to aid with the cooling of the room. Along the south wall to the room there was originally a collection off heat producing apparatus, coppers over here to the west side, holding hot water, the central cast iron kitchen range [originally here], and secondary ovens for streaming and the like to the east side. With all of these devices firing, it could get so hot in the kitchen that staff could pass out. The sides of the skylight are pivot windows intended to be opened so as to cool the room.

Around the kitchen you can see further archaeological evidence of what was originally here. Centrally located to the east wall we retain the original pot dresser to the room. On the north and west walls there is evidence of where shelving and cupboards were once located. Over in the far corner is the scullery to the kitchen, which originally housed the sinks where pots and pans were cleaned. In time we will reinstate copies of these items. Aside the pot dresser, you can see doorways, one to the right and two to the left, the last of these being in the scullery itself. These doors lead into further vaults, akin to those at the front of the house. The two north most vaults both stored coal, exclusively for kitchen use, the south vault was rendered and lined with shelves, to provide for a milk and cheese larder. All three vaults lay beneath our stable, with the coal being delivered to the two north vaults via chutes inset to the stable floor.

Stables. Within the stable, which opens onto Brunswick Street East, (the next road to the east of the Square), on the ground floor was found a carriage stand, a harness room and six stalls for animals, while over, at 1st Floor level, there were haylofts and accommodations for the coachman and groom. With the division of the last Brunswick Square houses into apartments in the post-World War Two period, the stables to the properties were sold off into separate title, being turned into flats and commercial garages. Sadly, this leaves us without ownership of this important part of the original building and no prospect of taking you up into the stables for a look at the equine architecture thereto.

The Brunswick Town Houses are on average are 35 feet wide, 70 feet tall and 140 feet in plot length. Their construction made the best of the land Thomas Scutt owned, massively increasing acreage value and placing here, some of the very best quality terraced housing built in the period.

We see our mission at The Regency Town House as talking about his important part of our local heritage, and illustrating appropriate ways to maintain this legacy, without the need to resort to modern plasters, cements and the other impervious building products of our age that do more harm than good to historic buildings.