R-EX data Tour transcript - edited

The Regency Town House

The Regency Town House is developing as a small heritage centre for the city, one that’s focused specifically on Brighton & Hove’s urban architectural legacy - the fabulous terraced architecture forming the Squares, Crescents and Parades for which Brighton became famous some 200 years ago.

The Regency Town House research is interested in the lives and homes of ‘ordinary people’ in the early 19th century. These include the rich, powerful, characters living upstairs in houses lke this one. Also the rapidly-developing middle classes of the period, such as the architects designing new homes and the lawyers negotiating property sales, as well as those at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum, such as the artisans working in the building industry, the servants employed in homes like this, and the proverbial butcher, baker and candlestick maker.

We don’t have a lot of money to spend on our renovation program, so work here depends heavily on volunteered time and effort. Each year we move a little closer to presenting a fully-repaired house> In time this will offer some rooms that are finished and furnished to original specification and others where visitors can explore a mix of educational resources about 18th and 19th century history.

We offer tours of The Regency Town House, these can be booked through our website.

The tours look at the transformation of Brighton from a coastal fishing town to a fabulous and fashionable resort, they explore how property in Regency Brighton was built and decorated and how those in fashionable society lived upstairs in houses such as this; finally, they contrast the lives of those living upstairs with the people working downstairs on their behalf, taking a look at the domestic rooms in our basement property at No. 10 Brunswick Square.

Regency

There are two different definitions of the term 'Regency' and this can cause confusion. In a strictly political sense, the Regency is a short period, starting in 1811 and ending in 1820. During This is when the King at the time, George the Third (also written George III or George 3rd), was considered to have lost his mental capacity to govern and so his eldest son, also called George, was made the 'Prince Regent' and acted as head of state in his place.

When George was the Prince Regent he was sometimes refered to by the nick-name 'Prinny'.

Following the death of King George the Third in 1820, George the Prince Regent inherited the crown and became King George the Fourth, bringing the political Regency to an end.

King George the Fourth is also written George IV or George 4th.

In contrast to the political Regency, 1811 - 1820, the term 'Regency' is also used in a stylistic sense, to refer to a far broader timeframe, generally considered to start in the late 18th century and continue through to the middle of the 19th century.

The development of Brighton

Let us explore the transformation of Brighton from a coastal fishing town to a fashionable resort. The origins of this process lay further back in time that the stylistic Regency, as it is through the early part of the 18th century, the 1720s, 30s and 40s, that Brighton first starts to undergo development as a spa resort.

The picture 'Lambert’s view of Brighthelmstone' was originally published 1765. This is several decades after spa development first began in Brighton but the town has not changed significantly. in the picture we see a town with a population of some 2,000 people, a market garden area to the north of the town and the adjacent downland being cultivated for crops.

If we move forward 14 years and look at a map of the town made in 1779, we can see the town is bounded by the main streets that exist today: West Street, North Street and East Street. Behind the town, you can see some of the market garden area.

If we move forward 30 years and look at a map of 1808 we can see that the town has spread significantly beyond West Street, North Street and East Street and buildings now cover the area previously used for market gardening to the north of Brighton and to the east of the Steine.

In 1808, Hove village sits about a mile to the west of the Parish boundary with Brighton and is a tiny village, with a total of some 200 residents.

In a watercolour painting of the early 19th centruy, Hove village is a distant ribbon of development, separated from Brighton by agricultural land.

In a map published in 1827, some 20 years after the 1808 map, one can see how much Brighton has flourished, with lots of buildings to the west, north and east of the 'old town'.

In maps of the mid-1820s we see for the first time Brighton’s two great ‘new town’ developments, Kemp Town to the east and Brunswick Town to the west.

Brighton’s development through this period can be measured by its growing population: in the mid-18th century Brighton had around 2,000 residents, by 1808 the population was more than 10,000 and by 1827 it was nearly 30,000.

Two paintings of Brighton, one made in 1819 and another in 1839 bring home very powerfully how fast Brighton was growing through this period - by some measures Brighton was the fastest-growing town in Great Britain at this time.

Two reasons for Brighton's popularity at this time:

The first reason is attributed to Dr Richard Russell, a British-born, European-educated physician, who worked locally for most of his professional life. In 1750, Russell published his book 'Dissertation on the Use of Sea Water in the Affections of the Glands'. This book became hugely popular and encouraged people to use seawater to cure all sorts of illnesses and aflictions.

The 'seawater cure' involved far more than simply bathing in salt water. The process was made mystical and complex, so that patients would be forced to pay a large fee to consultants or doctors, who claimed to know how to bring about a cure. the doctor would tell the patient exactly when and for how long they needed to bathe in the sea, or drink salt water, often mixed with things like milk, tar, crushed crabs eyes, burned coral and many other compounds.

The second reason for the success of the town is due to ‘George’, initially the Prince of Wales, subsequently the Prince Regent and ultimately, George the Fourth (George IV).

George Prince of Wales first visited Brighton in 1783, when he was aged 21. George liked what he found in Brighton and returned regularly until the last few years of his life. He was shaping and overseeing the construction of the magnificent Royal Pavilion in the process.

In relation to Brighton’s development, it is argued that George's presence in the town attracted fashionable society and gave Brighton a social, economic and aesthetic edge over other evolving seaside spas.

The 1825 drawing ‘Beauties of Brighton’ by artist George Cruickshank illustrates members of fashionable society promenading in front to the Royal Pavilion.

Another factor in Brightopn's transformation into Europe's premiere seaside resort was the improvements to transport through the second half of the 18thcentury and the first half of the 19th century, shortening journey times to Brighton and lowering the cost.

Visitors at that time found a more relaxed attitude to social interaction, allowing people to more easily make new connections, explore opportunities for the marriage of their children, and seek improved financial investments.

The expansion of Brighton also brought opportunities for financial speculation, a massive rise in the provision of services and the improvements made to the town’s race course, gambling establishments, circulating libraries, assembly halls and housing stock.

Houses in the little streets to the east of the Steine were constructed in the late 18th century as Brighton’s first purpose-built visitor accommodation, to ensure that visitor had somewhere to stay and prevent Brighton losing out to rival resorts. The rate at which building developement accelerated in the early 19th century is demonstrated by the move away from building relatively unambitious small homes in little streets, to constructing whole new-town projects on the scale of Kemp Town and Brunswick Town.

Charles Busby

When we look at the development of Brighton the early 19th century, we must consider the role of the architect Charles Augustin Busby. Born in 1786 to Dr Thomas Busby and his wife Priscilla, Charles Busby was the principle architect that shaped the development of late Regency Brighton. More of today’s listed architecture is designed by him than any other, including the two great estates of Kemp Town and Brunswick Town.

Living in London, the busby family were social and political radicals of the age, with close attachments to some of the most talented figures of the period. Within their social circle were Willian Blake, Lord Byron and Merlin the Ingenious Mechanic. While working as a professional musician, a translator of Latin and Greek, and a newspaper correspondent, Dr Busby and his wife home-educated their children through to their teenage years, at which point, what they considered their natural aptitudes were identified and the children articled them into relevant professions.

For Charles Busby the selected route was architecture and trained in the drawing office of Danial Asher Alexander, one of the Regency's great designers. Busby was also fortunate in that he was admitted to the Royal Academy's school, then a fairly new establishment. In 1807, aged 21, Charles Busby graduated the Royal Academy with their Gold Medal, demonstrating his status as an outstanding talent, and he left Alexander's drawing office to embark on an independent career.

Charles Busby's career was going well and, having inherited his parent's radical social and political views, rether than undertaking the traditional 'Grantd Tour' of Europe to further his learning, he embarked on a boat across the Atlantic, landing in Manhattan. He lived for a period in Wall Street and Nassau Street during which he joined the great scientific institutions of the city and contributed drawings to Blunt’s, 'Guide to the City of New York', published in 1817.

Charles Busby travelled through the Eastern Seaboard states of the USA, meeting the great and the good, recording interesting American construction projects, and contributing his own architectural designs at the request of clients. He returned to the UK during 1819.

Shortly after his return to ther UK from the USA in 1819, it is thought that Charles Busby visited Brighton for the first time, most likely at the request of Thomas Reed Kemp, then one of the richest men in Sussex. Kemp was seeking to develop a large new town project to be named after him, and it’s thought that he wanted a top-flight architect to co-design the scheme, together with a local builder and architect, Amon Henry Wilds. The two men’s work for Kemp was completed fairly quickly as, once the designs were produced, Kemp made it clear that he would oversee the building of the new estate and that he had no further need of the pair.

Amon Henry Wilds and Charles Busby sought employment elsewhere around the town and found many commissions, but they dissolved their short-term business partnership amid some acrimony.

Building Brunswick Town

Within a year of the Kemp Town project starting, Charles Busby had agreed with another local landowner, the Reverand Thomas Scutt, that he would participate in a second large-scale building enterprise. Scutt’s land lay to the west of Brighton, on the south-easternmost corner of the Parish of Hove.

The ‘Memorandum of Agreement’ to build Brunswick Town was signed by Charles Busby and the Reverand Thomas Scutt on 11th November 1824 and, thereafter, large scale works were very quickly underway.

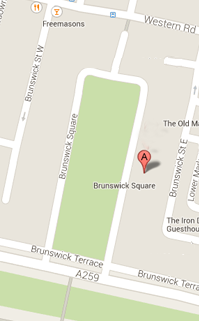

An early plan drawn by Charles Busby illustrates how Brunswick Square forms the centrepiece to the Brunswick Town estate, with large houses for affluent residents around the square and continuing along the coast road to the east and west to form the Brunswick Terraces. Around these grand terraces there are mid-sized properties forming streets for the middle classes, including Waterloo Street and Lansdowne Road and, around these, are grouped smaller properties to house the working classes.

For the different socio-economic groups coming into Brunswick Town, Charles Busby designed and built what he considered the appropriate infrastructure. This included a chapel, a public bath, the Kerrison Arms Inn, (a family hotel for the more affluent visitor) and a covered market and shopping district. To the west of Brunswick Square he built police and fire stations and an office for the Brunswick Commissioners.

The Brunswick Commissioners were a group of men who, under the powers granted to them in the Brunswick Town Act, governed the estate. It’s worth reinforcing that the ‘Parliamentary Act for Brunswick’ shows that the development was considered a town in its own right.

Busby had great talent but little money, while Scutt had both land and money, but he was reluctant to risk his fortune on developing Brunswick Town alone. Instead, the two men set about employing the ‘urban speculative development model’ to enable the construction.

The ‘urban speculative development model’ recruited investors to risk their funds and build to Busby’s designs and building regulations. The hope was that this would result in well-designed buildings that would make money for all concerned. To attract investors, Busby produced what are called ‘client drawings that illustrated the fine properties that it was proposed to build.

We have one of Busby’s client drawings which shows both the front elevation of the house and its plan form. Along the bottom of the page that there is handwriting that reads: “Plan of Mr Charles Elliot’s house Brunswick Square, agreed for £3,000 to be finished complete”. Beneath this, the document has been countersigned, on 5th July 1827, by Geo. Wil. Sawyer (George William Sawyer). He is the builder employed by Charles Elliot to construct the house. The two men have turned the document into a contract with the agreed price for the job. In addition, across the sheet, on top of Busby’s annotations, they are writing in the details of the room finishes to be supplied for the construction fee. In the front basement room, a brick floor is specified; in the ground floor front room, which is the dining room, the finish is described as ‘stucco and paint’; on the first-floor main rooms, which are the drawing rooms, the decoration is with paper at one shilling per piece; while in the upper storeys the quality and cost of wallpaper is reduced.

Charles Busby exercised control over the whole build process, producing detailed drawing for the construction process. These included written instructions about the making of foundations, details of the mortars and renders to be employed, the dimensions of the main timbers in the property, and much more besides. In another drawing we can see Busby’s attention to detail. Here, he notes the size of windows, the directions and dimensions of floor joists and how to reinforce cellars where this is thought necessary.

House interiors

We can see the interior of a large Brunswick property during the Regency period in a series of sketches produced in 1840 that illustrate the interior of No. 32 Brunswick Terrace.

In a sketch of the ground floor front room, the dining room, we can see the corner of the main dining table and a half of the sideboard. This is a south-facing room and through the partially open window we can see some of Brighton’s fishing fleet at work on the sea. The windows are finished internally with poles and drapes, wooden venetian blinds (which were very popular at the time), and sun or ‘snob’ screens. These screens attach to the lower part of the window and articulate with them as they are moved. The screens were often made from green silk and provide privacy in rooms that have a pavement directly outside.

There is an oil lamp on the sideboard. Although gas pipes were run underground in Brunswick Town to power the street lighting, many house owners were initially reluctant to use gas inside their homes because they were afraid of possible explosions.

Another picture shows the drawing rooms. Here there is a better quality of decoration, including a ‘Brussels weave’ carpet fitted up to the skirting boards; a ‘drugget’ (a type of thin rug) covering the expensive carpet to protect it from day-to-day wear and tear; curtains with pelmets which, by the late Regency, had become very fashionable. There are also a fortepiano and a flower stand, showing the increasing importance of interior plants.

A third drawing illustrates the second floor of the house, where the principal bedrooms and dressing room were located. Here we can see the main bedroom containing a large, fashionable bed, a washstand and commode, and a dressing table with chair and mirror. There is an expensive carpet on the floor.

The painted plaster walls and timber fittings would have been complimented by silk curtains in the formal rooms of the house. Fitted carpet was available in late-Regency homes but were generally not used in areas where people ate - as rugs were easier to lift and clean.

The drawing rooms

The drawing rooms are on the first floor of the house. This level of the property was generally developed to provide for a front and back Drawing Room - albeit occasionally the rear room could be purposed to serve as a bedroom.

The front and back drawing rooms each have their own door. This is so they can operate as two seperate rooms when the folding doors between them are closed.

There would be folding doors between the front and back drawing rooms. The doors, in four leaves, were mounted on ‘Parliamentary hinges’ that enabled them to be part-opened, or folded all the way back to join the two rooms into a single suite. The folding doors, in four leaves, were mounted on Parliamentary hinges so that they could be part opened or fully folded back to co-join the two rooms into a single suite. During the daytime, the doors were often left closed.

In the morning, the rear drawing room perhaps being used by the ladies of the house for reading, writing, sketching and the like. While in the afternoon, children may have rehearsed with musical instruments in the front drawing room. By the time children were being sent to bed, and the family were in full entertainment mode, the doors between the two drawing rooms would be thrown open, so that after a meal in the Dining Room, guests could gather in groups across the increased floor space, and settle in for a few hours of convivial conversation.

Georgian families paid a premium to obtain a house to the ‘preferred east side of a square’, because the orientation of the property to the position of the sun throughout the day meant they would outlay less money on artificial lighting over the course of a season.

Because the drawing rooms were co-joined in the evenings, the two parts were very often decorated as a single suite, with matched ceiling centres, cornices, fireplaces, skirting boards, curtains, carpets and wall decorations. This is how we believe these two rooms were treated and, by looking at the original fabric still visible in the front room, you gain an idea of the original finish.

What you’re looking on the front drawing room walls is the second layer of oil paint ever applied. The underlayer being plain and, we think, not used for very long. As you can see, we have a geometric scheme here, with pinkish-brown panelling applied to a grey background. If you look closely where the two colours meet you can see puncture marks in the plaster. At a very high level of magnification, tiny fragments off gold can be found here. This suggests that around each panel there was originally a gilded, timber moulding. There is visible archaeological evidence of where picture frames once hung in left and right panels of the main wall and the wall opposite. In fact, in the panel to the right of the fireplace, you can actually see evidence of the cord that was suspending a frame in this location, the ‘shadow’ of the cord forming an apex that drops to either side of the frame.

The centre panel on the main wall has the shadow of a much larger frame. You can see the mounting points for this along the base, the left and right edges and the top of the frame, with corners clipped at 45 degrees. This frame held a mirror, strategically placed to work with the windows inset to the bow front of the property, allowing the occupants of the house to view an ‘idealised nature’ through the windows, including a view of the sea - the windows and mirrors combining to bring the land and the water to the inside of the home.

Having paid £3,000 to develop a property Brunswick, ‘finished complete’, you’d acquired glass in the windows and fireplaces in the rooms, but the house was otherwise bare. Your next step was to furnish the home to the required standard. For this, you needed rugs and carpets, furniture to sit on top of these, paintings for the walls, baubles and instruments for the fireplace mantle shelves, (Chinese porcelains, European soft pasteos, and clocks, for example) and, of course, mirrors and chandeliers. Some of these objects could be hugely expensive, perhaps each costing as much as 10-15% of the build cost of the property.

Above the drawing rooms were the bedrooms and dressing rooms of the house, generally finished to a lower standard that the public reception areas where guest were entertained but, nevertheless, all demanding further outlay. Additionally, of course, you needed transport (horses and carriage) and your domestic staff, all of whom needed livery and meals provided.

The original occupants

It was very expensive to occupy a seafront property in Regency Brighton. Any suggestion that you might be financially challenged in doing so, would quickly result in you being ‘cut’ from society. Who were the original occupants of houses in Brunswick Town? Who were the people rich enough to meet the costs of being here through the height of the season? If we turn to the directories and other records of the period we can discover the early residents; people like the Duke of Bedford, possibly still the richest Englishman in Great Britain, the Duchess of Dorset, Earl Whitworth, and Princess Lieven, the wife of the Russian Ambassador.

Interestingly, even for the wealthy owners of Brunswick houses, there was a point at which excess expenditure was reigned in and, here in the front Drawing Room, we have an example of this. The room appears to be detailed in satinwood, in the architraves fitted to the windows and doors and in the skirtings. But not even the richest in society actually thought it made a great deal of sense to fell satinwood trees in Asia or Africa and import them to Europe for the purpose detailing interiors. Rather, the expensive joinery seen here is an illusion of paint and stain, applied over moulded softwoods. If we visit the Royal Pavilion and admire the acres of satinwood detailing there, it's the same, it’s all a decorative effect. Besides the financial saving, it allowed the owners of the house to respond quickly to changing taste. If rosewood or walnut became the new fashionable finish, a specialist painter could be called in and, by the time you staged your next soirée, a completely refreshed interior could be presented to guests.