24 Brunswick Square

24 Brunswick Square from Google Streetview

Like many of the grander properties in Brunswick Town, 24 Brunswick Square has seen a wide variety of inhabitants. In the first one hundred years or so, the heads of household were born in, or had careers spanning, the British Empire (as it then was) and included the ubiquitous military types and civil servants. But they also include the more colourful and unexpected, such as a bona fide operatic diva and a man you might be interested to hear more about if you are a follower (or player) of the modern game of tennis. And for the romantics there are three stories of love in older age. There are also tales, happy and sad, about some of the many servants who lived there.

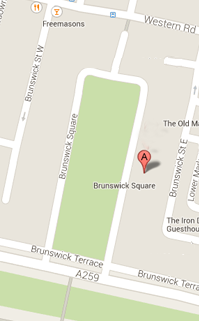

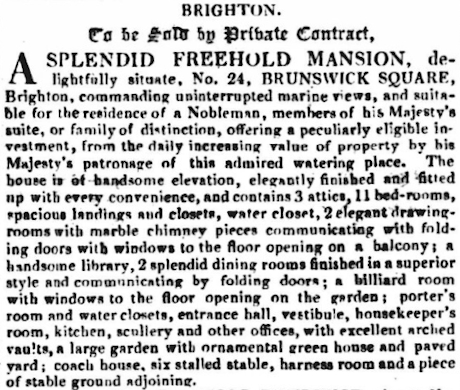

We first come across the house in a newspaper advertisement for sale in September 1830. It was built to appeal to “a nobleman” or “family of distinction” and was very well provisioned. There were 11 bedrooms, two drawing rooms, two dining rooms, a library, a billiard room, several water-closets etc as well as the necessary supporting facilities such as housekeeper’s room, kitchen, scullery and so on. The house had its own coach-house plus a six-stalled stable. Unusually, it also had “a large garden with ornamental greenhouse”.

Brighton Gazette - Thursday 23 September 1830

We don’t know much about the early inhabitants of the house. In the 1841 census there are only 2 servants listed as living there and I could not find out much about either of them. The early rate books show that the owner was William Stanford. He was the heir to Preston Manor and died in 1853. However, there is nothing to indicate that he ever lived in the house. Perhaps he was one of the many people who bought a house in Brunswick Town as an investment.

William Digby Seymour was the head of household from 1848 to 1852. In the 1851 census he was described as a 45-year-old merchant, born in London. He lived in the house with his wife Emily, who was the same age. They had a son Walter, age 17 born in Clapham and two daughters, 10-year-old Emily and 7-year-old Catherine, both born in St Pancras. They had six servants, who were all unmarried: Emiline Darke, age 26, a governess born in London; George Cox, age 31, a footman born in Hounslow; Ann Kirby, age 37, a lady’s maid born in Wilton, Wiltshire; a 28-year-old cook from Sandwich, Kent (whose name is illegible); Susana Jones, age 23, a house maid from Brecon and Eliza Racking, age 20, a house maid from London. As is often the case, none of them were born locally. The Seymours did not live in Hove for long and had returned to London by the time of the next census. However, despite not appearing to have close links to the area, both William (who died in 1872) and Emily (who died in 1866) are buried at St Andrews, Hove.

The next known occupant was Metcalfe Larkin, who took out a lease on the house in 1857. The lease is from the trustees of Wm Stanford Esq, deceased. It’s for 21 years (with the option for Larkin to terminate it after 7 or 14 years) and the rent was £160 pa (around £9,500 today), payable quarterly. It stipulates that the exterior must be painted every three years and the interior every seven years. Basically, the property had to be maintained “as is” for the duration of the lease, including regraining, revarnishing, repapering, etc. (For those readers not familiar with graining, it was a popular method of painting cheaper types of wood to make them look like more expensive varieties.)

Wood graining example

The lease also included measures to maintain the elite tone of the area. For example, Larkin was not allowed to advertise any trade, business or calling and must not have a “shop window”. Furthermore, he isn’t allowed to carry on any trade or business in the house (although it isn’t obvious how that could be policed). The associated schedule to the lease is a delight of micro-management, with very detailed itemising of the house contents down to the number of shelves in rooms, the number of bells (presumably to summon servants), etc. Some of the detail is interesting, however. The schedule lists the dimensions of the stoves in the rooms, from 12-inch stoves at the top of the house (where some of the servants would sleep) to a 31-inch stove in the front chamber. There is no mention of stables or other outside buildings, so it is possible that these were already being used for another purpose. (As an aside, it is interesting to note that lease restrictions had been relaxed slightly by the time of the 1870s. We know, for instance, that Dr Withers Moore was allowed to work as a doctor at number 18 Brunswick Square and to advertise that with a name plate on the front door.)

Metcalfe Larken died in the house on 13 August 1860, age 48. He had previously worked in the Bombay Civil Service as a judge. His first wife Emily had died aged 28 and he lived in the house with his second wife Sarah (she was 18 when they married in 1846, he was 33). Sarah (nee Pennycuick) had been born in Bengal, India. Many years after Metcalfe’s death, in 1882 when she was 54 years old, she received a pension of £360 pa from the Bombay Civil Fund (part of the East India Company & Civil Service Pension system). That is equivalent to about £24,000 now and ended with her death on 19 April 1889.

The next inhabitants were the Orreds. In the 1861 census, the head of household was George Cavendish Orred, married, age 53 (born 1 May 1807). His occupation was Major Militia and he was born in Lancashire. We know that George was a landowner (he was shown in an earlier census as Landed Proprietor). His 48-year-old wife Matilda was born in Southwick, Hampshire. They had married in 1838 in Fareham. Also living in the house are their four children. 19-year-old John Cavendish Orred was born in Forres, Moray and was in the Royal Lancers. The other three were 14-year-old Charles Stanley; 22-year-old Matilda, born in Florence and 15-year-old Selina. The family was obviously very mobile and to continue this pattern they only stayed in Hove for a couple of years. George died in October 1869 in Lucerne, Switzerland.

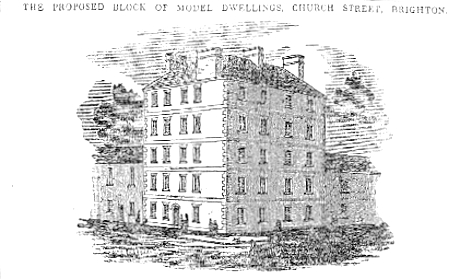

At the time of the census there were two visitors, but I could not identify them clearly. There were also six servants. Of these, the ones I could identify clearly were Henry Smith aged 48 from Buckinghamshire and 34-year-old Charlotte Smith (unmarried) a housemaid born in London. Henry Smith stayed in Brighton but seemingly had a tough life. In the 1871 census he is a domestic butler, living at 43 Borough Steet (which he shares with his family and another domestic butler). He is married with 4 daughters and 2 sons. In the 1881 census he is an unemployed waiter, now aged 69 and widowed, living with one son and one daughter at 10, Model Dwelling House. And in 1891 he is in the workhouse, a general labourer. He probably died in 1897.

Plans for the Church Street Model Dwellings from Brighton Gazette of Thursday 23 September 1830

The Model Dwelling House that Henry lived in no longer exists, but there is still a similar one in Church Street, Brighton. According to Wikipedia, “Model Dwelling Companies were a group of private companies in Victorian Britain that sought to improve the housing conditions of the working classes by building new homes for them, at the same time receiving a competitive rate of return on any investment”.

The Orreds were followed by two other short-term residents, namely The Dowager Lady Gordon and Sir Orford Gordon, who lived in the house in 1864 and 1865. However, the next resident, John Moyer Heathcote, stayed much longer and is an interesting character.

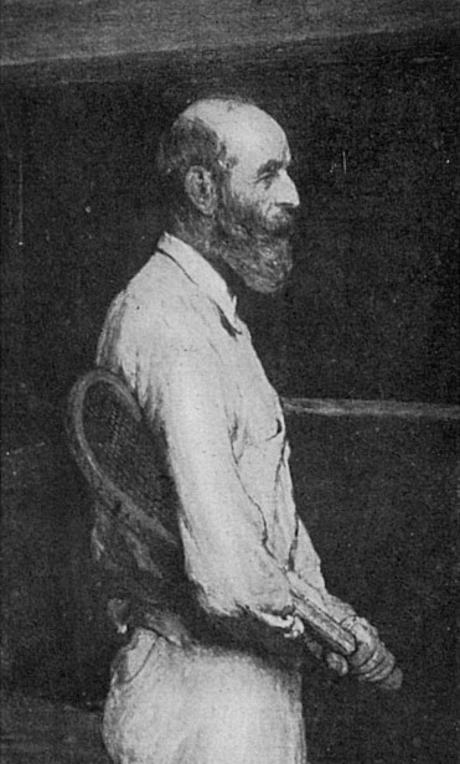

He moved into the house around 1868 and by the time of the 1871 census was a 36-year-old JP and barrister, born in London. He was well known for being the best “real tennis” player of his time. (Real tennis is the original racquet game from which modern tennis derives.) He was one of the committee members at the Marylebone Cricket Club responsible for drafting the original rules of lawn tennis and is credited with devising the cloth covering for the tennis ball. In 1871 he was living in the house with his wife Louisa Cecilia, age 32, also born in London. They had three children: daughter Emily Louisa age 9 born in London; son John Norman age seven also born in London and daughter Evelyn May age five born in Brighton.

John Moyer Heathcote

Like some of the previous occupants, they also had 6 servants: Augusta Gould, a 25-year-old unmarried governess from Petworth; John P Miller, age 30, a butler from Mayfield; Elizabeth Ann Bettridge age 60, a cook from Chelsea; Mary Ebdon, unmarried, age 37, a house maid from Somerset; Ann Markness, a 21-year-old nurse from Northampton and Lizzy Fairy, age 16, born in Connington, Huntingdonshire, a kitchen maid. I was not able to find out much about Lizzy but Connington is the ancestral seat of the Heathcote family so she was probably known to them.

Augusta Gould is one of our stories of late love: she married Edward Temple in 1884 (aged 39) and gave birth to a daughter, Elfrida, when she was aged 44 in 1890. Edward was a widower colonel in the Indian Army. They eventually lived in Poole, Dorset where Elfrida tragically died of the flu at age 29 (in 1919). She had been a Red Cross ambulance driver in France during the First World War and had been awarded an MBE shortly before she died. Edward died in 1926, aged 87. Augusta survived her husband and daughter and died in January 1940, age 94 leaving just over £1000 (around £39,000 today).

Elfrida Temple

The Heathcote family’s cook Elizabeth Ann Bettridge (nee Sharp) was married to Thomas Bettridge, a butler of the same age. In the 1851 census, they were both in the employ of Thomas A Garth (age 54) at 37 Brunswick Terrace (just around the corner from Brunswick Square). At that time, they had a 3-year-old daughter, also called Elizabeth. In 1861 the family were living in an area of Marylebone where there were lots of other servants and tradespeople, but they did not live in the house of their employer. In the 1881 census Elizabeth is a housekeeper/domestic servant in Cockfosters. She probably died in Brighton in 1885. Thomas had died in 1882.

Mary Ebdon stayed in the area. She died in 1909, living at Farm Road, and is buried at St Andrew’s. In the 1881 census she is a housemaid at Palmeira Square and in 1891 she is a housemaid in Hove. It seems that she never married.

Unfortunately, the Heathcote family were away at the time of the 1881 census, so we don’t have any specific data for the inhabitants then. All we know for certain is that John, the son, was at Eton. The family left the area in 1884, selling their furniture and effects by auction in March. A newspaper advertisement gives a broad description of the items for sale. My favourite is a “full-compass cottage pianoforte in rosewood case (by Chappell)”, which sounds charming. John Moyer Heathcote died in 1912, leaving just over £112,000 (around £8.75 million today).

In the 1891 census, Thomas Dodd Milburn, age 52, is the head of household. He is a retired major “living on means”. He had retired in 1874 and moved into the house around 1885. He was born in Crawcrook, Durham. Also living there was his wife Jane Crawford Milburn who is 10 years younger. She was born in Montreal but is a British subject. They were married in Montreal in 1867. He was then Assistant Surgeon, 13th Hussars. He had been admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons in 1861. Jane’s father was a shipping and railway magnate. The Milburns have only one servant, Kate A Barnell, an unmarried 23-year-old housemaid born in Brighton. I was unable to find out anything more about her. The Milburns moved out around 1893. Thomas died in Kensington on 16 Jan 1919 leaving over £33,000 (over £950,000 today). The beneficiaries were his two sons, Claude Edward Allan and Hugh Ernest Spencer, who were both in the Army.

The next head of household was Robert Wilfrid Graham, who moved into number 24 around 1896. He was a civil engineer who had worked on the railways in India and is our second story of love in older age. At the time of the 1901 census he is obviously away. The only residents listed are 3 servants: Alice Bradley, single, age 39, a cook from Brighton; Isabella Adams, age 44, single, a housemaid born in Hailsham and Mary Joynson, age 16.

Alice, born in 1862, had also been working in Brunswick Square in the 1881 census, but then it was at number 11. In 1911, she is living at 9 Grand Avenue Mansions, Hove. She is a cook and the other resident is Annie Hughes, a 24-year-old housemaid born in Firle. Alice died in December 1922 when she was living at Livingstone Road, Hove.

Isabella Adams was born in 1857. In the 1861 census she is living with her parents Peter and Caroline in Hailsham. She has two sisters and three brothers. Her father is an agricultural labourer, also born in Hailsham. By the 1871 census she is a housemaid (age 14) in Lewes. The head of household is John Willett, a farmer. In the 1881 census she’s a housemaid in Marine Parade, Brighton. Willett is given as the head of household so she obviously moved with him. In the 1891 census she’s a housemaid, back in Lewes. The head is William Mannington, age 59, a retired farmer. In 1911 she’s a housemaid in Second Avenue, Hove. She stayed in the area and died in 1924, living at 5 Goldstone Road, Hove leaving just under £600 (around £24,000 today).

Mary Nellie Joynson was born in 1884 in Willesborough, Kent. Her father was a labourer. By the time of the 1911 census she is living with her family again, in Ashford Kent, described as a general domestic servant. She has one brother (John, age 22) and one sister (Jenny, age 24), all 3 of them single. The final resident is 7-year-old Frank, described as “grandson”. Evidently, Mary had had a relationship with a footman (Arthur Playford) and gave birth to a son. However, it seems that Frank was later put into the care of the Barnardo’s home in London (possibly around the time Mary met her future husband). Frank tragically died of acute bronchitis in 1915 on board a ship en-route to Canada with other Barnardo’s children when he was only 11 years old. Meanwhile, in 1914 Mary had married 39-year-old William Foad (whose first wife had died in 1911). Together they had 4 children and she died in Thanet in 1932, when the youngest child was only 10 years old. William died in 1948, age 72.

Returning to Robert Graham, much of the information we have about him has been taken from “Grace's Guide To British Industrial History”. He was born at Arthuret, Cumberland, in 1823. We know that he spent a considerable period in India, starting in or before 1850. For example, in 1856 he is recorded as a qualified civil engineer working in Bombay, and he was appointed a Fellow of the University of Bombay in 1862. In 1866 he wrote a book called “Description of the Bhore and Thul Ghat Inclines, on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway'”. This might sound like it would only be of interest to train-spotter types, but there is tragedy behind the story of that part of the line.

The East India Company was contracted to build and operate the line and Robert Graham was one of two assistants to the Chief Resident Engineer. Work started in 1850 and initially there was very slow progress. However, the first part of the line opened in 1853. The Hull Packet newspaper reported in early 1866 a “... frightful accident on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, at the reversing station of the Thull Ghaut (sic), which resulted in the instant death of six or seven persons, and the serious injury of another. Just before coming to the scene of the accident there is a declivity varying from 1 in 100 to 1 in 37. All that is known of the circumstances is that the train, as it came down the gradient, obtained tremendous velocity, rushed past the station so rapidly that nothing but its momentary whirl was heard, dashed through a barrier at the end of the rails, and literally leaped down the precipice beyond. One of the guards jumped off and was terribly injured; but the other poor fellows who were in charge stuck to their posts and were killed in the crash. Scanlan, the guard who jumped off, is not considered to be in immediate danger, but his jaw being broken, he is unable to speak.” I do not know if Graham’s book makes any reference to the accident.

As mentioned earlier, however, there is happier news associated with Robert Graham. On 21 February 1888 he married Anna Maria Gordon Mackenzie. She was a widow 14 years younger than him - he was 64 at the time. Anna was born in Quebec and so there is another French-Canadian link to the house (see Jane Milburn above). Robert Graham left the house around 1908 and died on 20 April 1917, leaving just over £28,000 (over £1.6 million today).

For a while after the Grahams moved out it is not entirely clear who was living at number 24. There is a gap in the street directories and there are only two occupants of the house in the 1911 census: Edward Brown, head of household, a 61-year-old bathchairman and his 64-year-old wife Mary Ann, who is a caretaker. He was born in Wedmore, Somerset and she was from Tonbridge, Kent. They had been married for 20 years and were childless. It seems unlikely that a bathchairman (someone who pushed people around in bathchairs, a forerunner to wheelchairs) could afford to live in such a large house. Perhaps the Browns were employed to live in and maintain the house. I could not find out much about them.

Example of a Victorian bath chair

There were no such problems with the final resident of the house during the period covered in this article. She is our operatic diva, Margaret Fanny MacIntyre. She was known by various other names, including Fanny Margaret de Halpert and Margaret Fanny de Halpert. For simplicity, I am referring to her as Margaret.

She was born in November 1863 at Waltair, Madras, India to Scottish parents. She was a Victorian opera singer who had studied in London and made her debut in 1888 as Micaela at Covent Garden, where she sang regularly until 1897. Margaret’s many roles included Donna Elvira (in Don Giovanni), Ines (in L'Africaine), Mathilde (in Guillaume Tell), Aida, Marguerite (in Faust), Marguerite de Valois (in Les Huguenots), Elsa, Senta, Elisabeth (in Tannhauser), Desdemona, Leonora (in Il trovatore) and Santuzza. She created the role of Rebecca in Sullivan's Ivanhoe at the Royal English Opera House in 1891. She took her role as Elisabeth in Tannhauser to Moscow and St Petersburg. She also sang numerous times for Queen Victoria. In a newspaper interview in 1896, Margaret explained that she had received several gifts from the Queen including “a lovely gold ornament of an angel with exquisite diamond wings”.

Margaret Macintyre

She was obviously something of a trailblazer. She sang Sieglinde at La Scala in the first Milan performance of Die Walkure (1892): the first time a British prima donna had performed there. She made her only Metropolitan appearance (in New York) as Margherita (in Mefistofele) in 1901 where, apparently, she was the first British prima donna to have impressed in the USA. She also toured and sang in South Africa.

Unfortunately the trailblazing was not always positive for Margaret, as it seems she also had what we would nowadays call a “stalker”. In 1891 there was a court case involving Levy Nicholas Darlington Pickett, a 28-year-old organist. He was charged with sending a letter “threatening to kill and murder” Margaret. Apparently, they had never met but about three years earlier he had started writing to her and even sent “some articles” to her, which were returned. Margaret’s mother had met with him and asked him to stop, but he didn’t. The letters then progressed to marriage proposals and, finally, the death threat. In court, Pickett’s defence council said that the accused expressed “his deep regret” and undertook to stop writing to Margaret. The main thrust of the defence was that at the time he wrote the threatening letter “his mind was off its balance”. He changed his plea from “not guilty” to “guilty” and undertook not to repeat his actions. The judge then bound Pickett over, which effectively means he was given a suspended sentence. “If he behaved himself properly, he would not hear anything more about it. If he repeated the offence he would be sent to prison.” And that was the end of the matter.

Things did improve for Margaret, though, as she is also our final story of later love. She married Felix George de Halpert in Dover in 1907 when she was aged 44 and he was about 29. He was a minor Polish aristocrat but I have not been able to find out much about him.

It is unclear when she first moved into 24 Brunswick Square. We know she was in the area in 1911 and was obviously connected with the house because a planning application was made on her behalf to instal a lift at the rear, going from the ground floor to the third floor. At the time, her address was given as Lion Mansions Hotel, Brighton. She was certainly living in the house in 1912 because there was another court case involving her, this time as the defendant. She was being sued by Hudson’s Limited (a furniture removal company) for £130 10 shillings and 10 pence (about £10,200 now) for the removal and marine insurance of furniture and household effects from Berlin to the house in Hove.

At the heart of the dispute was the use of a fourth delivery van, which Margaret said she had never agreed to. The original quote, which Hudson’s made without seeing the goods needing to be moved, was to use three vans. When they arrived in Berlin, they found that the furniture wouldn’t fit into three vans and said that Margaret agreed to a fourth being added, at the same rate as the other three. She claimed that she was not told about the fourth van at the time and did not agree to it being used. The cost of the fourth van made up about £2,500 of the total being sued for; Margaret was happy to pay the rest. She obviously had a poor view of the entire operation, saying “ten of the roughest looking men entered and tore over the flat like madmen, picking up anything they could take hold of. There was no order or system, the things being literally thrown into the vans by the Germans”. However, she lost the case.

According to the street directories, Margaret left the house around 1918. In the meantime, however, very sadly her husband died on 12 March 1916 (aged only 38), leaving £1600 (around £95,000 now). The Times report says he died “very suddenly” … “beloved husband of Margaret Macintyre de Halpert”. She herself died aged 79 in 1943 at 'The Old Manor', Salisbury, Wiltshire. She left £14,103 (around £500,000 now). The National Portrait Gallery has three pictures of her.

Research by Teresa Preece (March 2024)

Return to Brunswick Square page