Brunswick Street West History

Brunswick Street West was built as a service road for the properties in Brunswick Square and Brunswick Terrace West. The street supported the facilities and accommodation for the people who provided services to the gentry.

Click here to explore how the numbering has changed in Brunswick Street West over the years.

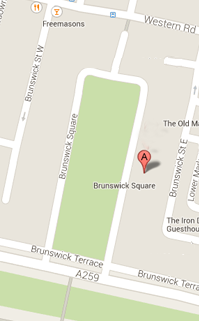

Geography and history of the street

C.A. Busby’s 1825 Plan for Brunswick Town. From ribapix.com

Busby’s scheme for Brunswick Town shows the east side of Brunswick Street West was planned to be individual stables and coach houses for the houses on the west side of Brunswick Square and the south spur of the road for stables at the rear of Brunswick Terrace West. The plan also shows the Star of Brunswick public house with a cottage opposite at the northern end of more stabling at the rear of the garden where Lansdowne Mansions would be built by the 1850s.

There were two modest buildings just to the west of the pub which would be used as Green Grocers and Bootmakers.

The west side of the street in Busby’s plan is described as Ground reserved for general purposes. Unlike Brunswick Square, the houses in Lansdowne Place were not designed with their own stables at the rear. It seems that there was no coherent development strategy for the section of Brunswick Street West to the north of the Star of Brunswick. More pubs, shops and the Police Station were built there later but the street numbering is difficult to follow, particularly as the two east-west spurs are sometime named as Brunswick Mews and Lansdowne Mews as opposed to Brunswick Street West.

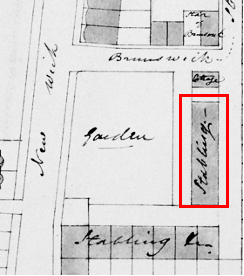

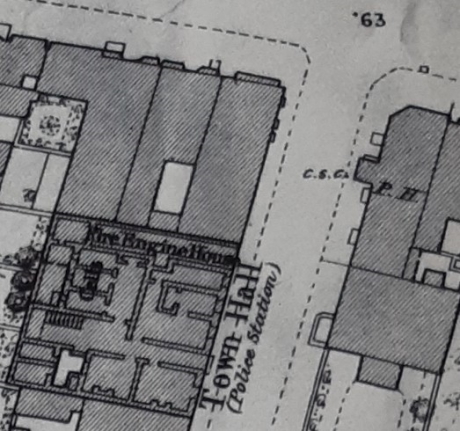

1875 Ordnance Survey map

The above map shows that there was a somewhat unequal distribution of properties on the eastern side of the street. The northern half from 32 at the top (northeast corner) south to 46 where part of the street turns west had spaces for a potential 16 stable block buildings. In 1875, however, 7 or 8 of these were still shown as not being built upon. The southern part (47 southwards) had 11 spaces – all of these were built on.

The 1841 census identifies 10 uninhabited buildings on the east side and these are likely to be some of the stables.

It’s also possible that the enumerator considered the stables to be part of the main houses in Brunswick Square so would be enumerated there.

Fire / police station and Commissioners’ Room

The Commissioners for the Brunswick Estate were created by the 1830 Brunswick Square act and held their first meeting in April 1830, in the Kerrison Arms Hotel on Waterloo Street.

The estate soon needed permanent meeting facilities as well as a fire station and somewhere for the watchman to live. During the first months of 1831, the Commissioners discussed how to provide such accommodation.

On 17 January 1831, the committee resolved to find land to build housing for a well, pump for watering the district, a shed for water carts, a fire engine and a room for the commissioners to meet in. A week later they reviewed four pieces of land and chose a site in Brunswick Street West owned by C.A. Busby. The land was located within 50ft of the Western Road on the west side. They recommended purchasing 35ft of frontage from N. to S. and 51ft from E. to W.

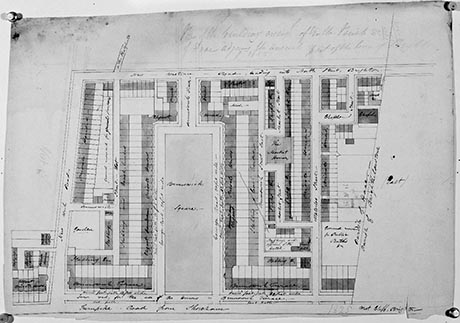

For the building itself, the surveyor, T.W. Clisby, presented two options: one, a single storey building housing the well, water carts, fire engine and a private entrance leading to steps to a second floor if required; and, secondly, a two-storey building with the same ground floor plan plus a second floor comprising accommodation for the Watchman, a tank for the water carts and meeting room for the Commissioners.

The two-storey building was chosen and it was agreed to buy the land from Mr Busby for £280 and tenders were advertised for the building work.

Plan of the ‘Ground Floor for a Pump House etc'. From the RIBA Drawings Collection

The above drawing of the ‘Ground Floor for a Pump House and Well, Sheds for Water Carts, Engine / House' is a copy by Busby of an original design by T.W. Clisby.

By August 1831, the commissioners were seeking tenders for watering the district with the water carts being supplied by the commissioners. The provider of the watering service was, however, required to keep the well sufficiently deep to ensure a plentiful supply of water.

The Commissioners’ Committee Room was opened with the first meeting on 12 September 1831.

The commissioners minutes of 5 January 1855 show them agreeing to purchase Mr Martin's house directly to the south of the original building which, along with his house, was demolished to make way for the new Hove Town Hall. This new buidling wich is still in existence today opened around 1855 or '56 and stretches a further 15ft to the south of the original commissioners' room. The southern boundary of the original building being at the northern side of the new main door opening.

The Station Inn (now the Bow Street Runner) first appeared in 1867 and is situated next door to the Town Hall. Previous owners have claimed that the pub was built on the site of the first police station, a claim which is, unfortunately, untrue as the pub site was always some way to the south of the original Brunswick Commissioners’ 1831 building and south of Mr Martin's house.

Livery Stables

Livery stables would have been ideally situated to provide suitable transport for Brunswick Square residents who may have preferred the 19th century equivalent of our own hourly street car hire as opposed to the expense and inconvenience of maintaining their own carriages, horses and coachmen. This would apply particularly to visitors to the Square as well as some of the long-term residents. Also, there were no stables built at the back of the Lansdowne Place houses so they would have needed the services too.

In 1853, the following advertisement for three sets of properties appeared in the local newspapers:

HIGH VAULTS used as COW LODGES, with Buildings at end, and large Yard, enclosed by Folding Gates, situate in BRUNSWICK STREET WEST, HOVE, extensive Stabling over same, comprising three four-stall Stables, one three-stall ditto, two double Coach Houses, one large ditto for eight Carriages, large Lofts and Rooms over. Let on Lease to highly respectable Tenants, at £80 per annum. Also, a Cottage at the end, Let on a Yearly Tenancy of £15. The extent of this important range of buildings is 145ft. by 40ft. 3in.

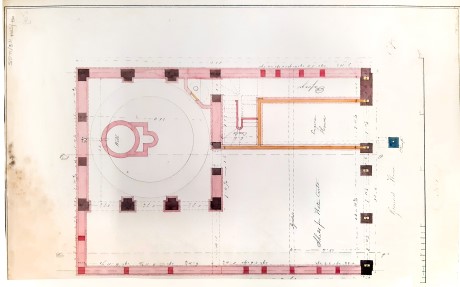

1875 map detail

The advert is describing the area in the south-west corner of the street east of the Garden (which became Lansdowne Mansions and then the Dudley Hotel).

The reference to the High Vaults, Cow Lodges and Cottage in the first paragraph point to this area being next to the Garden on Busby’s plan, where Lansdowne Mansions (later to be The Dudley Hotel and now Dudley Mansions) were built. The stabling became the Lansdowne Livery Stables. John Egerton was resident at the Lansdowne Livery stables in 1851 and appears in the newspapers in following years selling horses and harnesses from the stables. The stables were three storeys high and would have been one of the largest buildings in the Brunswick Estate.

Read more about the Livery Stables.

From the construction of the street in the 1820s for most of the following century, the properties on the east side of the street were stables, often with coach houses and accommodation above, for the houses on the west side of Brunswick Square. Some of the Brunswick Square houses weren’t built with stables and, instead, had gardens at the back.

Apart from number 32 at the top, all of the stables were physically linked to the Brunswick Square houses which meant that, generally, any of the coachmen, grooms and their families were recorded in the census entries for the main houses. Unfortunately, number 32 is only connected by a path behind Western Road to its house, 32 Brunswick Square, and this seems to have resulted in any occupants being ignored by the census enumerator on his travels on the assumption that they would be counted in the main square.

History of the Street

In modern times we have come to expect that the numbering of our streets is fixed and unchangeable. In Georgian and Victorian times things were less standardised, especially where new roads and streets were carved out of open land. When piecemeal development took place, it was common for numbers to end up out of sequence (where infilling took place) or when it came to be realised that existing number sequences were no longer logical.

Moreover, in the early days of a new road’s existence it was common for some or all buildings to have no numbers whatsoever. This was eventually corrected by local municipal bodies in their pursuit of a logical, ordered and standardised society. The advent of postal services and the increased mobility of the population would have hastened such progressions.

Certainly, as far as the owners of houses in Brunswick Square were concerned, any stable blocks would have been part and parcel of the one establishment. This is borne out by the numbers still shown in one or two places in Brunswick Street West for those locations where an access continues from the street to the Square.

Door to 38B in Brunswick Street West (Courtesy of Google Streetview)

Between 51 and 53 Brunswick Street West is the door to 38B Brunswick Square - a reference to the previous numbering system.

The numbering of the west side of the street up until the 1920s started with the Commissioner's room at the northwest corner with no number followed by number 1 immediately to the south and increased going down the road, apparently independent of the numbering on the other side. In 1855 when Mr Martin's house was purchased to allow for the building of the larger new Town Hall, number 1 disappeared leaving number 2 (the future Station Inn) as the Town Hall's neighbour.

Up until the 1920s, the street numbering on the southern spur of the road, to the rear of Brunswick Terrace, and the eastern side to the rear of Brunswick Square, match the numbers of the main houses to which the stables belonged. So, for example, 29 Brunswick Street West in the southeast corner of the road is the stabling for 29 Brunswick Terrace, whilst 32 Brunswick Street West some 250 metres away in the northeast corner of the street is the stabling for 32 Brunswick Square.

In 1924/1925 the street was comprehensively renumbered with the lowest numbers in the sequence being given to houses at the southern end – the reverse of the direction of numbering until that date. This is also the opposite to the numbering on the western side where house numbers are lowest at the northern end (the Western Road end) and highest at the south (Brunswick Terrace end). In this renumbering normal UK convention was followed and odd numbers were allocated to houses on the eastern side with even numbers being used on the west.

On the east side, 32 Brunswick Street West became 67; 39 became 49 and 47 became 33.

On the west side, The Station Inn (1867-1912), 2, became 62; The Denmark Tavern (1867 to 1899), 5, became 54; the Star of Brunswick pub became 32; Munger’s Greengrocer (previously 2 or 3 in the 1850s, then 21 in 1898) became 30, and the next-door bootmaker became 28. The South Coast Motor Garage was 41 before 1925 when it became 36.

Infrastructure in the Street

An advert for watering the streets between April and October appears in the Brighton Guardian of Wednesday 14 March 1832.

An invitation to tender for the provision of Drainage and other works for Brunswick Street West appears in the paper on 28 August 1851.

Once neighbouring Brighton had become a Borough, the Brunswick Estate needed its own Town Hall which opened in 1855/56, containing courts, police station and fire station.

In 1877, the large livery stables, then owned by the Brighton Livery Stables Company, was put up for sale. The advertisement for the auction appeared on 12 December 1877 and describes the Lot as:

The Leasehold Stabling, Coach-houses, and Buildings situate on the West side of Brunswick Street West, Hove, comprising standing for 17 Horses, with Coach-houses, Granary, Lofts and Living Rooms

After Hove became a Borough, a new Town Hall, designed by Alfred Waterhouse, opened in Church Road in 1884. The original Town Hall was sold and by the 1890s had become the Pelican Club. This building is still in place in 2022.

The old Hove Town Hall at the top of Brunswick Street West in 1875

Residents and their occupations through the years

For the first century of its existence, the street and the occupations the residents were engaged in didn’t change very much. There were two or three public houses; a Green Grocer and Bootmaker’s shop; several female servants; a couple of dressmakers and one or two tailors.

Another constant through most of the period was the presence of the Brunswick Estate Watchman, George Breach. George lived in the street from 1835, moving into the New Town Hall in 1856. The census of 1841 records George Breach, age 30 from Steyning, as the Watchman for the Brunswick Estate.

George would later go on to become the Policeman and the Chief Superintendent of Police for the Brunswick Estate, living most of his life in Brunswick Street West.

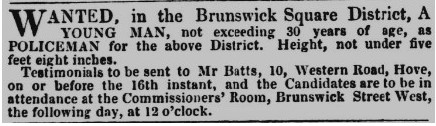

The advert in the Brighton Gazette of 10 September 1846 is, presumably, aimed at recruiting an assistant to George who, by the 1851 census, is the Superintendent of Police.

According to the Brighton Guardian, George celebrated his 65th birthday and completed 42 years of service on 5 January 1877. He was the Senior Police Officer in the Kingdom. He retired by December 1877 and moved to 39 Blatchington Road, Hove where he died in October 1888. He was succeeded by his wife, Caroline and son, George Benjamin.

The predominant employment in the street was associated with horse powered transport. As well as the stables backing onto Brunswick Square on the east side of the streets there were two or three livery stables for the use of those residents without their own dedicated stables and coachmen. Over the years, the census enumerator often missed the residents of the stables, either because they weren’t there when they called or because he assumed that they would be counted in the Brunswick Square census.

There seems to have been at least two livery stables in the street, the larger Lansdowne Stables and a smaller one run by James Matley. James had three brushes with the law: once as a defendant and twice as the plaintiff. George Breach wouldn’t have had far to go to investigate the three crimes.

The Brighton Gazette of 22 May 1845 reported a court case involving a Mary Ann Tims, a single woman of 15 years old, who was accused of stealing a shawl, the property of James Matley. Mary Ann was found guilty and, as she had a previous conviction, was sentenced to six months hard labour. Life was tough for 15-year-old women.

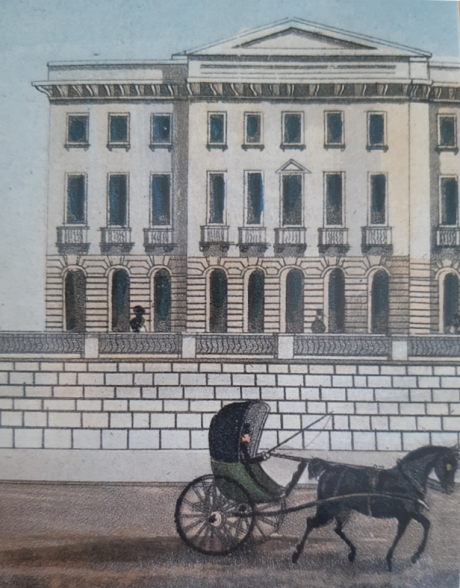

A small horse drawn carriage in front of Adelaide Crescent

In May of 1852, James Matley was in court again, this time defending a claim from a fly passenger, Edward Chilcott. A Fly was a single horse drawn, covered light carriage. The passenger agreed to hire the fly for 14s (shillings) so the livery stable allocated a driver, Henry Fuller, to take him on his journey. Chilcott asked to be taken to Steyning to see his girlfriend but on arrival, decided that he didn’t know where she lived. After an accident involving the fly, Chilcott rode the horse back to Hove and refused to pay the hire fee due to the accident. After some laughter in the court room, the judge found in favour of the proprietor, James Matley, and ordered Chilcott to pay the 14s.

In November of the same year, the Brighton Gazette, reported that James Matley was in court again, this time defending a charge of cruelty to animals. A passenger had reported a horse with injuries which were causing the animal some pain. Robert Read, a constable of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, examined the animal and found a large wound the size of a hand, and reported that it was evident the horse was unfit to work.

Matley blamed his fly driver for using the wrong saddle and claimed to have dismissed him. The magistrate still held Matley responsible and fined him 30s with the fine to be split between the informer and a charity of the court’s choosing, the Brighton Dispensary.

The number of coachmen found by the census peaks in 1871 with 18 and declines to 12 by 1911. There are also several cab proprietors, fly proprietors, livery stable keepers, stablemen and ostlers over the years.

Changes in Occupation

By the 1911 census there are four chauffeurs and a motor-cab proprietor. During the 1910s and 1920s the stables get converted to motor garages. By the mid-1920s, the street directories show a range of occupations dedicated to motorised transport including: Taxi proprietors, Motor engineer, Motor coach works and garages.

Over the century, the census also identified people with job titles that we probably wouldn’t recognise today:

1851 Census

Sylvanus Scourfield, a 49-year-old ex-serviceman, originally from Wales, is living at number 2 with his wife Martha from Hampshire. He’s described as a Chelsea out-pensioner so, he’s retired from a military career. Sylvanus might be the first person of modest means to retire to Hove and enjoy his remaining years without the pressure of having to work.

John Layzell, 55 years old, originally from Suffolk, living at number 9 (also known as Lansdowne Cottage) gave his occupation as Ostler, a man employed to look after the horses of people staying at an inn. Interestingly, John lived opposite the Star of Brunswick pub so maybe he provided a service to visitors to that hostelry.

Lansdowne Cottage in 2018

1861

Edward Peters at number 4 was a Fly Proprietor who, at the age of 42 was living with his wife, son and two other families. A fly proprietor was the owner of a one-horse carriage hired by the day. They would have been similar to Hansom Cabs.

A late-1800s Hansom Cab

The 1861 Census shows a complete sequence of buildings from 1 to 18 on the west side of the street. Within this unbroken sequence, numbers 7, 12 & 13 show residents’ occupations as Coachmen. A Groom was also found at 13.

A coachman was a man whose business it was to drive a coach, a horse-drawn vehicle designed for the conveyance of more than one passenger and covered for protection from the elements. A domestic coachman was usually employed by a gentry family, who had their own stables or a mews where the coachman and family would live above accommodation for carriages and horses. He would drive the family horse drawn vehicles, including a covered carriage, a barouche, a dog cart, taking the family on shorter journeys, visiting friends or to the station. In a great house, this would have been a specialty, but in more modest households, the coachman would have doubled as the stablehand or groom.

A Victorian domestic coachman and carriage – a “Barouche” or similar style

1871

On 3 April 1871, the ten-yearly census provides us with a snapshot of our small street in Hove - a tiny glimpse of so many individuals and their interwoven lives on one spring Sunday.

There are many fascinating things shown by the analysis, such as:

The variety of occupations of our residents – some are clearly business people working on their own account – Chief Superintendent Police, Beer Retailer, Fly Proprietor, Coal Merchant, Livery Stable Keeper, etc. Others are from the employed, working classes - servants, coachmen, labourers, dressmakers, milliners, etc.

Ages given for the two spouses are usually very similar, with some examples of a man married to a slightly older woman and vice versa, of course. But occasionally there is the large age discrepancy between husband and wife (an older man married to a younger woman).Traditionally Victorian society was beset by illness that caused many to become widows or widowers at an early age. With no provision for social services and with children needing domestic support it is unsurprising that there would have been a natural inclination for widowed individuals to find a new spouse.

Sarah Saunders at 6 – a 29-year-old widow with three young daughters aged 2, 4 & 6 and a servant - 12 years old Rose Peters. We can imagine that Rose looked after the girls, allowing Sarah to earn her living as a dressmaker. Ten years later the census shows that Sarah has moved within Hove/Brighton and that she is still unmarried and working as a dressmaker. Her two eldest daughters (now 16 & 14) are still living with her, but are now working as milliner and tailoress, respectively. No doubt they learned their trade by helping their dressmaker mother. Their additional modest earnings would have enabled the services of a servant to be dispensed with, until such time as they themselves married and left the family home. Despite her unmarried state, Sarah’s family has been augmented by the birth of a son – five-month-old Sydney Saunders. Let’s hope this little family survived all that life threw at them.

Two older unmarried men shown as lodging together in rooms at 4. James Marshall (69) no longer working, and Thomas Mackerel (62) surely coming towards the end of his career. One wonders what would their precarious financial hold on life in Hove bring next, once their earning power diminished?

The disparity between the occupations of men and women. Men are involved solely in jobs involving physically harder, manual type roles. Women are engaged as dressmakers & milliners - performing the less physically demanding tasks that were deemed suitable and acceptable in mid-Victorian society.

A large number of different households present within one building, these would not have been self-contained flats – simply sets of rooms rented out to boarders. Life in a multi-occupancy dwelling must have been cramped, noisy, probably dirty and stressful, one imagines.

The early age at which children started work - Ration Winham at 5, aged 14 is shown as working as a Porter for instance (perhaps working and learning his trade in his father’s Beer House at the same address). An analysis of those living in the richer households in the Square invariably shows that children of the well-to-do of a similar age were designated scholar implying that they were attending school.

The often large number of children contained in a single household – Mary Bailey at Edgerton’s Stables had her first child at age 26. She went on to have another five children, the last born when she was 38.

Many first-born children were given the same forename as their mother or father – a complication that besets the investigative work of researchers as they try to catch details of the lives of those they study.

One of the many households present at 3 was Henry & Rose Taylor. He was 48 and she only 28. Their family unit had just been increased by the birth of a first son, Harry Taylor who was aged 4 months on census Sunday. Henry was a porter – almost certainly a lowly paid job. The excitement of a newly created life and possibly, a recent marriage must have been constantly tempered by their reality of needing to continue to be healthy within a stable domestic and work environment. Life for the lower classes in Victorian Hove & Brighton must have been a struggle – any small change in personal circumstances could have easily have spelled disaster.

Another family with a young child were the Youngs whose dwelling was “Stables - rooms over same”. William 22 whose job was Coachman had married Elizabeth 25 - their union had been blessed one year before census day by the birth of a daughter - Elizabeth A Young. Did they perhaps imagine a peaceful and tranquil existence with just the three of them starting their new life together? The next census, ten years later in 1881 shows a different picture. By then Elizabeth had given birth to four more daughters and they had relocated to Beddington, in Croydon, Surrey. William continued in the same trade – being described as a coachman domestic/servant. By 1891 their fortunes seemed to have improved, potentially. At this date he was described as jobmaster (a person who supplied carriages, horses and drivers for hire) and they had moved to Harrington Road in Kensington, London. By then one daughter was no longer shown in their household (married perhaps?) but a new brother had arrived – unsurprisingly named after his father - William A Young. One might imagine the father’s joy at a long line of daughters being finally augmented by a son to carry his family name forward. And, at last, someone to kick a football with.

Staying as a lodger in Lansdowne Cottage is Henry Knaggs, 32, with his wife Emma and daughter, also Emma. Henry is originally from Yorkshire but has moved all the way to Hove to find work as a Butler.

There were occasionally unpleasant happenings in the street. In May 1879, William Eggs, a luggage porter at Hove railway station, purchased some oxalic acid from a chemist at 6 Waterloo Street and apparently committed suicide by drinking it in Brunswick Street West. The reasons behind this are not recorded.

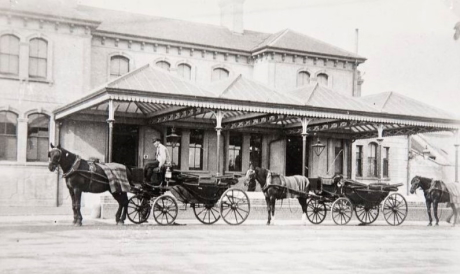

Hove Station in the late 1800s. From the James Gray Collection

1881

At number 4 was Ephraim Hopkin, aged 75, from Storrington, living with his wife and another family. Ephraim was a Handchair man who was likely employed to push invalid carriages. The hand designation distinguishes him from the donkey chairman who does the same job except used a donkey to pull the bath chairs rather than relying on manpower.

Next door at number 5 was 28-year-old William Liledot from Brighton living with his wife, daughter, son and mother. William was a servant employed as a Bath Attendant. It’s possible he was a Bathing Machine attendant but the fact that he’s a servant implies that he was more likely to be employed to transport his employer in a bath chair.

A bath chair was a light carriage for one person with a folding hood, which could be open or closed. Used especially by disabled persons, it was mounted on three or four wheels and drawn or pushed by hand. These were particularly used by invalids and people recovering from illness on their visit to the seaside.

A bath chair © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

1891

On census night in 1891, number 5 (the Denmark Tavern since 1867), is the residence of the beer retailer, and her son, one servant and eight lodgers. Once of the lodgers, Johnathan Robertson is 26 and describes himself as a Cordwainer, hailing from Sydenham, Kent. Jonathan would have been involved in the making of leather shoes.

1901 onwards

With the advent of motorised transport, the face of Brunswick Street West started to change from the beginning of the 20th century. Indeed, a visit to the street in 2022 shows that the smaller converted stable blocks are as useful today for ancillary motoring services as they were just over 100 years ago.

• Butcher’s stables (1905)

• Builder and Decorator (1906)

• Motor garage at 49 (1908)

• Automobile engineer at 49 (1909)

• Builders stores (1910)

• Fly Proprietor at 45 (1909)

• Taxi cab proprietor at 20 – Thomas Patrick (1910)

• Hairdresser (1912)

• South Coast Motor Garage (1912)

• Builders’ works’ offices (1912)

• Motor Engineer in Old Town Hall (1921)

• Motor coach works (1921)

• Ford repair and service centre (1923)

The transition from horse drawn to motor transport was swift. No doubt, like our own embracing of the internet and social media there would have been initial reluctance to switch to the new mode of transport. However, once ownership of motor cars had become an established and socially acceptable facet of early 20th century life, ownership in Britain increased rapidly, and local tradesmen responded swiftly to the needs of the owners of motorised transport.

“A gentleman's toy? In 1901 the motor car was still a luxury item, but it was an established, if controversial, phenomenon. Cars were still generally used for pleasure, rather than business, although they were becoming increasingly popular with regular daily travellers such as doctors. There were 23,000 cars on Britain's roads by the end of 1904, and over 100,000 by 1910.

Early motorists needed a spirit of adventure. Rudyard Kipling, who had owned a car since 1897, described car journeys as a catalogue of 'agonies, shames, delays, rages, chills, parboilings, road-walkings, water-drawings, burns and starvations'. Nevertheless, royal patronage helped to promote the fashionable 'necessity' of the motor car, which was a very visible sign of wealth.”

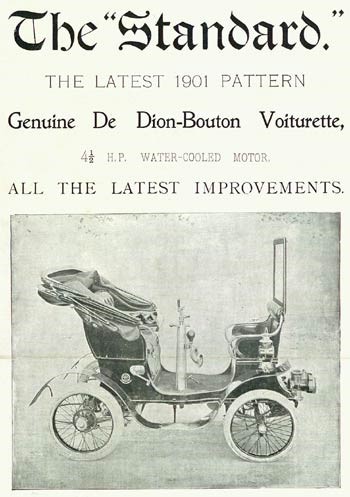

From this at the start of the 20th century, whose design with a foldable hood certainly echoes how carriages had previously looked...

1925 Ford Model T Touring Car

...to this at the time that a “Ford repair and service centre” was opened at 31 Brunswick Street West.

Research by Peter Hume and Kevin Wilsher, 2022

If you’re interested in getting involved with our history research, please contact the project leader at kevin@rth.org.uk